Ian Abbott on Pagrav Dance Company’s Kattam Katti

Posted: October 20th, 2020 | Author: Ian Abbott | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Gurdain Singh Rayatt, Hiren Chate, Kaviraj Singh, Nina Head, Pagrav Dance Company, Praveen Pratap, Simon Daw, Subhash Viman Gorania, The Motion Dance Collective, Urja Desai Thakore, Uttarayan | Comments Off on Ian Abbott on Pagrav Dance Company’s Kattam KattiPagrav Dance Company, Kattam Katti, Cambridge Junction, October 7

In the current political climate in the UK, making, rehearsing and presenting art takes courage because of the barriers the government are actively erecting to make it almost impossible for freelancers to survive and to not leave the sector — not only performers but also producers who are attempting to support dance, music and other performing arts.

There are many theories as to why this is happening, but financial return to the exchequer cannot be one of them. In the week I was invited to see a production of Kattam Katti by Pagrav Dance Company (PDC) in a closed performance at Cambridge Junction, Arts Council England published research by the Centre for Economics and Business Research that the value to the UK economy of the arts and culture sector is £13.5 billion and employs more than 230,000 people.

PDC has been working on iterations of Kattam Katti for over two years; it was originally due to premiere earlier this year at Sadler’s Wells with additional dates at Folkstone’s Quarterhouse and Milton Keynes’ MK Gallery. The company describes the work as: ‘Created by Urja Desai Thakore it transports its audience to Uttarayan, the world-famous kite festival that takes place in Gujarat, North India. Tales of competition, danger, excitement and unity in a landscape that wonderfully evokes both the solemnity and delight of this hugely important celebration are vividly brought to life…a neo classical work with a contemporary feel and strong roots in the South Asian dance tradition. It features original music, performed live, by four musicians who interact with and move around the four dancers.’

Offering employment for over 20 freelancers (4 dancers, 4 musicians, film crew, and production staff) for anywhere between a week and four weeks during this time is an act of courage; Thakore and creative producer Nina Head are to be applauded for achieving this. The performance I saw was three-and-a-half weeks back into rehearsal and the final two days of the week were dedicated to creating a new screen dance version by The Motion Dance Collective which will be released further down the line.

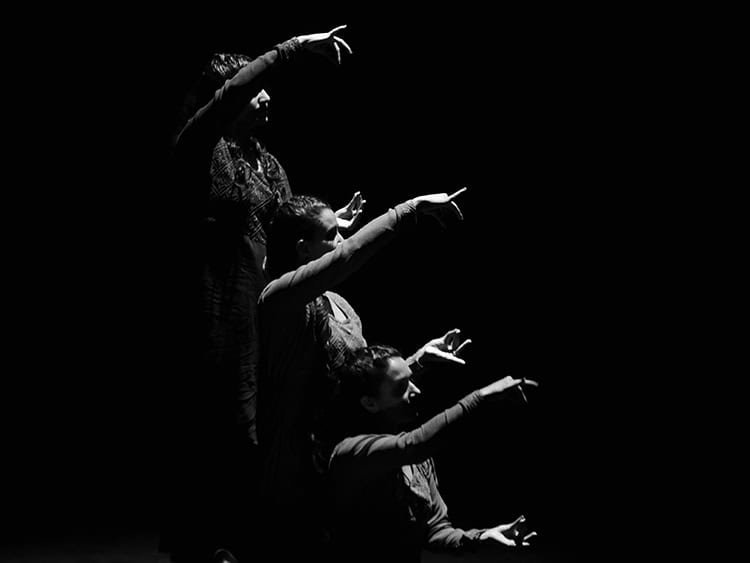

In 50 minutes, Thakore has created a snapshot of Uttarayan, a glimpse into some of the windows, characters, joys and physical rituals involved in making, flying, battling and celebrating kites at the festival. We see explicitly how the kites are constructed with the abrasive manja string that is coated with coloured, powdered glass that cuts your competitor’s string and, as Subhash Viman Gorania mimes, can cut your own skin, too. In the classical and contemporary kathak and bharatanatyam work I’ve seen before, musicians and singers are fixed either stage left or right and remain seated throughout the performance, lessening their presence and impact as live performers. What is refreshing in Kattam Katti is that the musicians are unfixed; they themselves are like kites traversing the stage on the winds of their own musicality, providing physical and aural emphasis to the choreography. Praveen Pratap on flute is particularly accomplished in his physicality and abhinaya whilst creating rippling melodies that cover the stage. The benefits of having the musicians and singers move — and move comfortably — around the stage is that Thakore has built her cast of 8 into an ensemble equivalent to the size of a Scottish Dance Theatre or Motionhouse production, creating a sense of theatrical scale to which this work could adapt in its future life.

There’s a suite of literary (Khaled Hosseini’s 2003 debut novel The Kite Runner) and wider cultural references around kites, Uttarayan and the idea of atmospheric flight that Kattam Katti sits alongside (Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam, a 1999 film by Sanjay Leela Bhansali has a whole song about Uttarayan, Kai Po Che, sung by Shankar Mahadevan and Kavita Krishnamurthy). The 2013 film Kai Po Che! directed by Abhishek Kapoor — the title is originally a Gujarati phrase that means I have cut — is a film based on Chetan Bhagat’s 2008 novel The 3 Mistakes of My Life which explores cricket, friendships and religious politics, but there is a scene that references the festival and offers a visual marker of how the city sky is covered in kites and how many thousands of people participate in it. There is genuine joy in the festival and on stage the sense of camaraderie between the entire company comes through; the ease with which they interact (especially in COVID times), trust each other and play with such grace is testimony to what Thakore has built in the rehearsal room.

The kite as a choreographic entity is fascinating and how it relates to Thakore’s primary kathak movement language is one of the most interesting aspects of Kattam Katti. A kite is steered by both the atmospheric conditions and the flyers themselves; it’s a constant and delicate negotiation, a balancing of conditions and ambitions to keep it in the air for as long as possible. A kite and a kathak body are technologies of movement and mobility; they’re not strictly directional and they are composed of loops, deflections and circles that can tell narratives whilst folding in and back on themselves. Whilst early on in the work we see the recognisable biomechanical movements of holding the kite, flying, tugging and keep the tension, the final sequence is quite brilliant in showing how these movements are fleshed out, built into and embellished using a wider kathak vocabulary. I wanted to see more of this bringing of the two movement worlds together rather than sequences of kathak followed by kitely recreations.

In some of the group kathak choreography, there is need for a little more polish and finesse in the execution of movements from a couple of the dancers, but each scene is elevated by the musicianship and compositions from Kaviraj Singh, Gurdain Singh Rayatt, Hiren Chate and Paveen Pratap. The musical arrangements are part of Thakore’s directorial role but the compositions are the work of each individual musician; Singh’s rhapsodic vocal work layered with Rayaat and Chate on the hypnotic udu and the beating rhythms on the kanjira for the dancers to ride give a visual and aural sense of being aloft. We are musically transported and immersed in an elemental space, shifting our perspective and scale to play amongst the kites; because the musicians are moving and playing the instruments around the stage there’s a three-dimensionality in play which adds so much to the visual world of Simon Daw’s moveable kite-tail, tangle-trip set design.

What is hinted at but feels like a missed opportunity is a commentary on class/caste. There’s a verticality in urban architecture and the Indian caste system where those who are richest (Brahmins) will predominantly own the tallest buildings, have access to penthouse apartments and therefore access to the wind. They are already at an advantage in the kite-flying stakes to the poorest (Dalits) who are deemed untouchable and who work in the streets. Having to mitigate all those structural inequalities to even get to a level playing field to engage in a fair Uttarayan could be further explored.

There’s room in the work for this, to stretch the characterisation and abhinaya of the dancers (or even creating a kind of sharks/jets relationship between the musicians and dancers) whilst acknowledging that it is a festival of joy, celebration and festivity. However, for 17 days of rehearsal, in the depths of a pandemic, with the concern around touch and transmission, Pagrav Dance Company has created a portrait of a fascinating festival, a work of lightness that rides the wind-soaked eddies; their crack team of musicians combine to elevate the work to a higher realm.