Posted: March 23rd, 2017 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Alejandro Virelles, Andrey Kaydanovsky, Daniele Silingardi, David LaChapelle, Icarus, Ilan Eshkeri, Jade Hale-Christofi, Narcissus and Echo, Natalia Osipova, Project Polunin, Sergei Polunin, Tea or Coffee, Valentino Zucchetti, Vladimir Vasiliev | Comments Off on Project Polunin: Icarus, Tea or Coffee, Narcissus and Echo

Project Polunin: Icarus, Tea or Coffee, Narcissus and Echo, Sadler’s Wells, March 14

Sergei Polunin, Alejandro Virelles, Daniele Silingardi, Alexander Nuttall and Shevelle Dynott in Narcissus and Echo (photo: Alastair Muir)

Sergei Polunin has long been interested in mythology. It could be said that his early life up to his departure from the Royal Ballet has elements of the myth of Icarus, and his more recent re-emergence in the light of Take Me To Church with the myth of Narcissus. It is perhaps no coincidence that Project Polunin should bookend its triple bill with works that reference both, though in terms of Polunin’s life there’s an important hiatus between the two.

With the recent release of Steven Cantor’s film The Dancer about Polunin’s life, it would be easy to imagine that Project Polunin follows on seamlessly where the film leaves off. But The Dancer took five years to film and another year to edit, so the film’s concluding performance of Take Me To Church — which at the time Polunin conceived as the final act of his ballet career — happened six years ago. A lot has happened in Polunin’s life in the intervening years; most importantly he has rediscovered his desire to dance and has gathered around him a group of creative people who have given him the confidence and stability to develop new projects. He is also, as evidenced in his Q&A following the launch of the film, questioning current norms in the ballet world with the proselytizing zeal of a reformer.

This premier production of Project Polunin consists of three works. As he explains in an interview with Sarah Crompton, “It shows what my thinking is influenced by…There’s an old Soviet ballet, a hint of dance theatre and…the kind of dance theatre I would like to explore.”

Expectations run high for an event like this, especially with the media attention from The Dancer. Will Project Polunin fly or won’t it? When Polunin discovered a video of Vladimir Vasiliev’s duet, Icarus, the night before the flight — created for himself and his wife Ekaterina Maximova in 1971 — it must have struck him as auspicious. Vasiliev had inspired the young Polunin with his powerful, passionate style of dance, and here was choreography with a mythical subject close to his own heart. Polunin extended an invitation to Vasiliev (Maximova died in 2009) to come to London to mount the duet on a younger pair of lovers, Polunin and Natalia Osipova. The choreography for both male and female equates powerful technique with powerful emotions, heroic form with mythological mettle. Polunin revels in the bravura steps, displaying the elevation and flight for which he is renowned and, as his betrothed Aeola, Osipova has so integrated her prodigious technique into her body that she can express every nuance of her devotion to Icarus as well as the depth of her despair suggested in Vasiliev’s choreography. Just to see these two together giving full rein to their Russian heritage is a privilege.

After only a brief pause we jump 45 years ahead to Tea or Coffee, served Russian style with dark and surreal humour. Choreographed by Andrey Kaydanovsky for four soloists from the Moscow Stanislavsky Ballet (Alexey Lyubimov, Valeria Mukhanova, Asastasia Pershenkova and Evgeny Poklitar), the ballet could well share the lineage of Nikolai Gogol with last year’s Royal Opera production of Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose, except that instead of the nose it is a cup of tea (or coffee) that seems to have a life and influence of its own. The work consists of four rounds of a game in which whoever starts by stirring the cup of tea (or coffee) is initially eliminated from the next one. Within this ludic format the two couples interchange and squabble over an unspecified but evidently banal issue which gives rise to is a delightfully absurd set of convoluted solos, duets, double duets and trios that borrow their wit and rhythm from the eclectic score.

The relevance of Narcissus and Echo as a contemporary myth is fully developed in the program by Ilan Eshkeri, where he quips, ‘Narcissus’ reflection in the pool is arguably the first selfie.’ Eshkeri also wrote the score (played live by members of the London Metropolitan Orchestra under the baton of Andy Brown) and his concept for Narcissus and Echo is credited as the starting point of the work. In a Polunin work about the power of the image it is not surprising to find the visual influence of photographer David LaChapelle, who conceived the video Take Me To Church. It is evident in the opening tableau of Narcissus (Polunin) and his four Theban mates (Shevelle Dynott, Alexander Nuttall, Daniele Silingardi and Alejandro Virelles), in the overall colour palette and in the surreal pond with its haze of light and outstretched arms appearing from below the dark water. It is less easy to discover the choreographic form of Narcissus and Echo. There are four choreographers listed: Polunin and his assistant choreographer, Valentino Zucchetti, Osipova (for her solo), and Jade Hale-Christofi (also of Take Me To Church fame) for Polunin’s solo. In such a sharing of choreographic initiative it is perhaps inevitable the story of Narcissus and Echo as Eshkeri conceived it is sublimated for a show of dancing inspired by its two protagonists with, in the case of Hale-Christofi’s contribution, ‘selfie’ quotes from Take Me To Church. Polunin, however, inspires his mates to excellence, especially Silingardi and Virelles (both on loan from English National Ballet), while the five nymphs (Alexandra Cameron-Martin, Maria Sascha Khan, Adriana Lizardi, Callie Roberts and Hannah Sofo) seem to operate in the shade of Osipova’s orbit. It is perhaps the first time seeing Osipova working out choreography on her own body, from subtle insinuation to blindingly powerful despair, and the result is sublime.

The similarity between The Dancer and Project Polunin is that they are both in the image of Polunin himself; Icarus has recovered but Narcissus is always going to be susceptible. As Eshkeri points out eloquently in his program note, ‘What is fascinating is how quickly the human condition allows us to become intoxicated with ourselves. And once engulfed by it how do we avoid the beguiling fate of our lamentable protagonists.’ Polunin is clearly trying to distance himself from his own image by paying his respects to his past, but he will need to find a new myth to define his next stage of development.

Posted: October 6th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Arthur Pita, Jackie Shemesh, James O'Hara, Jason Kittelberger, Luis F. Carvalho, Michael Hulls, Natalia Osipova, Qutb, Run Mary Run, Russell Maliphant, Sadler's Wells, Sergei Polunin, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Silent Echo | Comments Off on Natalia Osipova, Three Commissions

Natalia Osipova, Three commissions, Sadler’s Wells, October 1

Natalia Osipova and Sergei Polunin in Arthur Pita’s Run Mary Run (photo: Tristram Kenton)

Natalia Osipova is a dancer I could happily watch in any performance. Brought up in the Russian classical tradition, a supreme technician and dramatic presence, she is at home in the classical repertoire but itching to broaden her scope as an artist. Without retracting that opening statement, this evening of contemporary work for Osipova at Sadler’s Wells falls somewhere short of my anticipation. The issue is who commissioned this triple bill — first seen here in June — and why. Sadler’s Wells’ chief executive and artistic director, Alistair Spalding, suggests in the program’s welcome note that Sadler’s Wells commissioned the works, which happen to include two by Sadler’s Wells associate artists: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Russell Maliphant. In Sarah Crompton’s overview of the evening in the same program she makes it appear that Osipova commissioned the works. But if she did, why so early in her drive to broaden her horizons would she commission new works from choreographers she has already worked with (Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Arthur Pita) so recently? And is Russell Maliphant’s choreographic process likely to expand Osipova’s artistic range? I don’t think so. No, it is unlikely Osipova commissioned these works but has instead lent her name and talent — along with those of her partner Sergei Polunin — to the evening in return for the creation of three works brokered for her by Sadler’s Wells. It’s a compromise in which neither party comes off particularly well artistically; Osipova is not challenged enough because the works fall short of providing her with a vehicle for her scope. Cherkaoui’s Qutb thinks about it in philosophical terms but delivers a trio in which Osipova’s desire for flight is constantly grounded and smothered by the overpowering physique of Jason Kittelberger and in which the only (rather uninteresting) solo is given to James O’Hara. Qutb is Arabic for ‘axis’ but the axis of the work is Kittelberger not Osipova. Some commission.

Maliphant’s Silent Echo without the lighting would be like watching Osipova and Polunin consummately messing around in the studio. Maliphant’s choreography is so totally dependent on the lighting of Michael Hulls (a dependence that has become derivative) that any artistic development for the dancers is merely subordinate to the Maliphant/Hulls formula; the greatest hurdle for them is to dance on the edges of darkness.

Pita’s Run Mary Run is the only work in which Osipova and Polunin have roles to explore; Pita puts them centre stage in a musical narrative of love, sex, drugs and death to the songs of the 60’s girl group, The Shangri-Las. Known for their ‘splatter platters’ with lyrics about failed teenage relationships, Pita invests Run Mary Run with a theme of love from beyond the grave that he can’t resist associating — in the opening scene of two arms intertwining as they emerge from a grave — with Giselle. But Osipova’s persona is closer to Amy Winehouse (whose album Back to Black was inspired by The Shangri-Las and whose life Pita cites as the major influence for the work), and Polunin in his jeans, white tee shirt, black leather jacket and dark glasses is more like bad-boy Marlon Brando than a remorseful duke. While Pita’s narrative mirrors the destructive relationships in Winehouse’s life, the romantic elements of raunchy duets, flirtatious advances and feral solos feed off the partnership of the two dancers. Pita is pulling out of them elements of their own lives and putting the audience in the privileged position of voyeurs; we are living their emotions in the moment. This gives the work its edge and inevitable attraction. The colourful lightness of Run Mary Run — thanks to costumes and sets by Luis F. Carvalho and lighting by Jackie Shemesh — thus reveals a genuine heart that saves the work from its dark parody. But such is the nature of the heart that Run Mary Run may only succeed with these two protagonists.

Pita’s work is a step in the right direction for Osipova, as is the idea of her performing works outside her comfort zone. But if she really wants to find works that allow her more than an opportunity to dance a different vocabulary, she needs to find choreographers able and sensitive enough to fulfill her full potential by creating enduring works that are irrevocably stamped with her technical ability and personality.

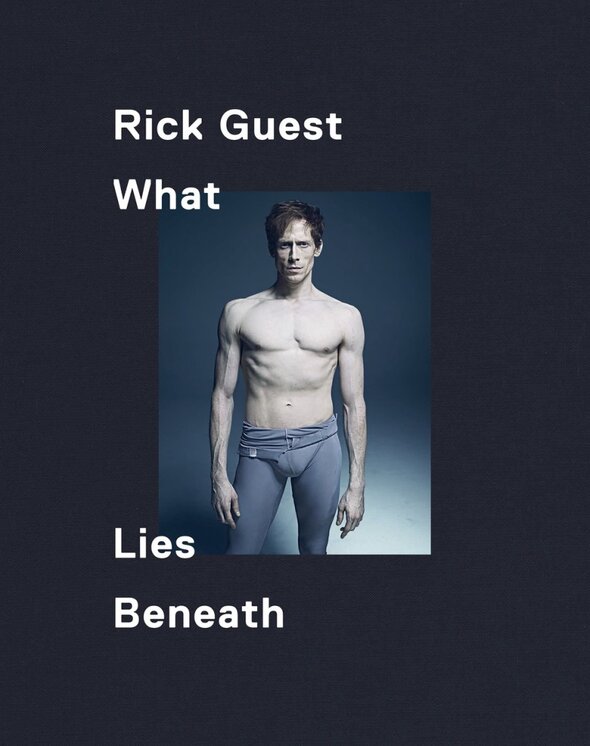

Posted: January 27th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Photography | Tags: Edward Watson, Rick Guest, Sergei Polunin, What Lies Beneath | Comments Off on Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath

Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath & The Language of the Soul

Still and moving images are the only ways of getting close to representing a memory of dance and it is only with the relatively recent development of recording techniques that the moving image has reliably captured artists in performance. The still image has been around for a lot longer, long enough, for example, to admire the series of photographs of Vaslav Nijinsky by Baron Adolphe de Meyer begun in 1911. In his sumptuous book of these photographs, Nijinsky Dancing, Lincoln Kerstein claims ‘Nijinsky is in fact the first dancer in history who seems to have collaborated consciously with a photographer on the level of art.’ Until the arrival of the 35mm camera and more sensitive film, the studio was where dancers and photographers would collaborate on a shared aesthetic but as soon as the technology was available dance photography turned its attention to the performance shot. Photographs of Royal Ballet dancers over the years show both kinds of images by such notable photographers as Gordon Anthony, Cecil Beaton, Anthony Crickmay, Michael Peto, Zoë Dominic, Keith Money, Lord Snowdon and Leslie Spatt while today you are likely to see glossy performance shots in the program by Johan Persson or Bill Cooper while in the contemporary sphere Hugo Glendinning and Chris Nash have developed a distinct style of expressive dance portrait that borrows from both performance and the studio. But at the end of last year fashion photographer Rick Guest released two self-published books of dance photography that eschews the performance for a more personal approach. Guest was introduced to dance by his wife some 15 years ago — he remembers Irek Mukhamedov in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet — and found his way back to The Royal Ballet with a commission to photograph principal dancer Edward Watson. From this grew the first book, What Lies Beneath, for which Watson is the muse and in which Guest’s fascination with and admiration for the dancer’s ethos finds expression in large-format portraits of an extended cast from The Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, the Danish National Ballet, Dresden’s Semperoper Ballett, Wayne McGregor’s Random Dance and Richard Alston Dance Company.

To concentrate his (and our) attention on the person Guest removes the locus of these photographs. All that outwardly signifies the dancer is the clothing, which is a study in itself: tattered, worn-out warmers that hang, it has to be said, with remarkable effect on these honed bodies or lovingly stitched repairs on a favourite unitard — as in the portrait of Melissa Hamilton that reveals the unequivocally trained body beneath its delicately scarred covering. In stripping the dancers of their performative role Guest reveals the enigmatic presence within. They are suspended not spatially (there are some fine examples of those, notably of Sergei Polunin suspended on an invisible cross) but psychologically; some have the confidence to be themselves in front of the lens, others feel the need to pose, giving the photographer their ‘best angle’ or baring their extraordinary physique for all time. But many are revealing of a quality that transcends description, of a neutral mien that is like the clay before it becomes a sculpted form (notably Svetlana Gileva and Julia Weiss of Semperoper Ballett). In other portraits there is an earthy quality that contrasts with the stage presence. Marianela Nuñez has a weightless, ethereal quality on stage but here she is quintessentially a woman with gravity in images whose locus is somewhere between the living room and the studio.

The dancers return our gaze — the gaze of the photographer — in response to a dialogue we cannot hear. Watson, like Hamilton, allows the gaze in, without any sense of defense. Eric Underwood looks into it as in a mirror; Yenaida Zenowsky and Yuhui Choe match it enigmatically, Alison McWhinney wistfully; Sergei Polunin meets it head on and Olivia Cowley gently deflects it. In Tamara Rojo’s reflective pose her eyes look away and down, preoccupied with her own world that is encapsulated within her superbly honed lines.

It is interesting to compare the physicality of dancers across the different companies — the effect of respective repertoires, physical conditioning and company culture. At Semperoper, for example, the dancers’ bodies appear more at ease and their clothing neatly utilitarian yet the traces of their profession are still apparent. What Guest has captured, essentially, is the way embodied classical training and the experience of performing express themselves in the eyes, in the posture and gesture of the dancer’s body. At the current exhibition of Guest’s photographs at the Hospital Club in Covent Garden, where the portraits are almost life-size, it is the eyes that engage directly with the lens and the spectator so they seem to follow you around the gallery.

In 2010 Guest saw Jane Pritchard’s Diaghilev exhibition at the V&A where his interest in fashion overlapped with his fascination for dance. The second compilation of photographs, The Language of the Soul, includes the same dancers as in What Lies Beneath but in more active poses partnered with his familiar world of fashion. ‘Some of the images are pure dance, some more fashion and some more photographic in nature,’ he writes. In both the dance and fashion portraits there emerges, unlike in What Lies Beneath, a performative quality which in certain cases is transformative.

There is a lovely anecdote in Sarah Crompton’s afterword to What Lies Beneath about Antoinette Sibley’s first glimpse of Galina Ulanova in rehearsal in 1956 that sums up the kind of place these dancers take up in Guest’s book:

“This old lady got up from the stalls. We thought she was the ballet mistress. She was saying something to the dancers and then she went and stood on the stage up on the balcony and she still had these awful leg-warmers on and, well, she looked 100. And then she suddenly started dreaming. And in front of our very eyes — no make-up, no costume — she became 14. I have never seen anything, in any sphere, as theatrical as Ulanova getting up in her scrubby old practice clothes…with her grey curly hair and becoming Juliet….From then on…I knew you could be…an amazing ballerina…and not perfect. Perfection was not part of Ulanova’s scene at all. She was human. It was to do with transformation.”

There are no ‘old ladies’ of either gender in the book, but some of the portraits reveal this transformative ability, notably in Sergei Polunin. He is singing in his portraits; he has something to sing about and so does his body. He becomes someone else. It is also good to see the performance photograph of Johannes Stepanek in an image I have seen in a Royal Opera House program without finding a credit.

The more I look at the photographs in these two fine compilations the more I am drawn into them. It is too easy to take the performance image for granted: to acknowledge the dancer without seeing the person. What Guest does is to first decontextualize the dancer and then to show each one in a refreshingly unfamiliar light with the immediacy of bringing the viewer into the same room to share his sense of admiration and awe.

http://rg-books.com/products