Posted: July 29th, 2018 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aitor Throup, Autobiography, Ben Cullen Williams, Company Wayne McGregor, Jlin, Lucy Carter, Nick Rothwell, Rick Guest, Uzma Hameed, Wayne McGregor | Comments Off on Company Wayne McGregor: Autobiography at Sadler’s Wells

Company Wayne McGregor: Autobiography at Sadler’s Wells, July 26

Wayne McGregor © Rick Guest

In the program for Company Wayne McGregor’s Autobiography, dramaturg Uzma Hameed writes eloquently about the ideas and processes by which McGregor arrived at this creation. It is one of the finest introductory essays to appear in a Sadler’s Wells program, but while Hameed addresses the semantic significance of each of the elements of the title — Auto/self, Bio/life and Graphos/writing — that clarify the creative input, what she does not and cannot address is the choreographic form these ideas take and their effect on an audience.

McGregor has never been one to favour clarity of meaning in his choreographic oeuvre. However, from her inside knowledge Hamzeed reveals some of the elements in his life that have influenced his choice of choreographic material — ‘a school photo, a poem about Icarus, a family history of twins, an Olivier de Sagazan film, influences of Meredith Monk, Robert Irwin, Beckett, Cuningham and more’ — but she also acknowledges McGregor’s ‘sense of continuous palimpsesting aspects of life encoded in choreography, overwritten by genetic code, in collaboration with software architect Nick Rothwell and transforming in every iteration.’ Add in the substantial collaboration of musician Jlin’s eclectic score, of set designer Ben Cullen Williams and lighting designer Lucy Carter and the contribution of costume designer Aitor Throup and the palimpsesting takes on the complexity of a genetic code. Where is McGregor in all this? It is, after all, the sequencing of his own genome that forms the basis of the work. In sitting through all 23 episodes of Autobiography at Sadler’s Wells the answer is everywhere and nowhere.

Everywhere because this is what he continues to do in his projects for his own company: mine the scientific community for inspiration and collaboration then create a work with fine dancers and high production values that is overdosed on inspiration and underpowered in terms of choreographic invention. The suggestion of an interesting work always appears as the curtain rises but there is a self-indulgent gene in McGregor’s work that quickly degrades the sense of cutting edge to déjà vu; the process has become formulaic. Atomos was based on cognitive science, Autobiography on genetics.

And nowhere because in invoking the fragment as a structural form of autobiography linked to his genetic code McGregor loses himself in the science. The fragment has been the trope of self-narrative for decades as writers and artists have used it to convey the layered and idiosyncratic experience of being. As Roland Barthes would have it, the body is the text. By leaning on the science of the body, McGregor uses choreographic fragmentation to reveal aspects of his biography but ends up concealing them under an inexhaustible appropriation of ideas, steps and gestural phrases that borrow from classical ballet and yoga with little contextual meaning. His genetic inspiration reveals itself in a vocabulary of hooked limbs and arms and rotating torsos that evoke the movements of chromosomes and their diagrammatic visual rendering (as does the lighting), but by overloading the language of his dancers with a pseudo-scientific aesthetic McGregor renders their expressive bodies — and thus his own autobiography — paradoxically bland; he retreats into a notional authorship that lacks the authority of ‘auto’ and the pathos and idiosyncracy of ‘bio’; what is left is the grandstanding ‘graphos’.

In the program there is a photographic portrait of McGregor by Rick Guest; he gazes over our left shoulder into the distance with his eyes closed, viewing his inner landscape while appearing to be present to our gaze. This stance is symptomatic of Autobiography. Rothwell’s software includes an algorithm based on McGregor’s genetic code that decides the order of the 23 sections; this evening the algorithm places section 1, titled Avatar, at the beginning but each evening the order will be unique. For McGregor this is thrilling because ‘the piece suddenly becomes a living archive of a collection of decisions,’ but for an audience that sees the work only once it is simply a solipsistic conceit that doesn’t take into account the inherent rhythm and punctuation of each section, not to mention its lighting and musical cues. If the opening section this evening feels like an opening, the last few have the flagging pace of a never-ending end; lighting effects overlap, musical tracks butt against each other and the choreography becomes an exercise in prolonged absurdity. Perhaps that is the cost to the audience of giving McGregor the satisfaction of playing with his algorithmic toy.

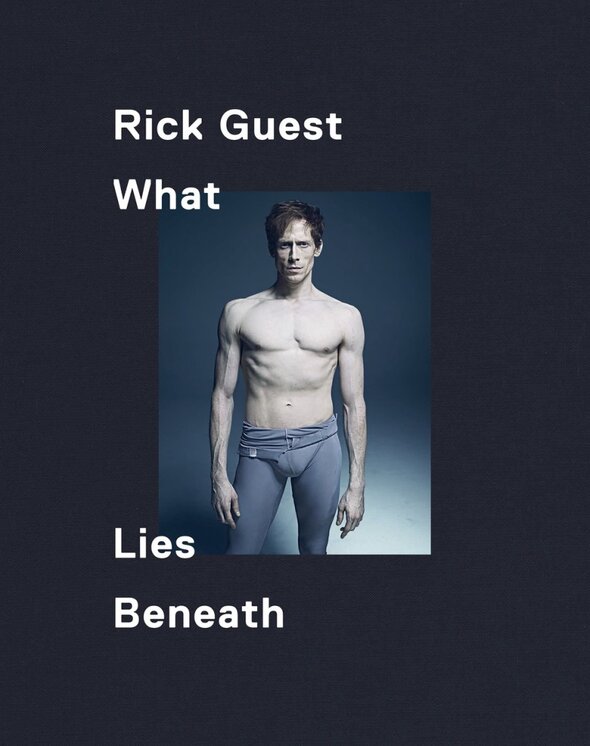

Posted: January 27th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Photography | Tags: Edward Watson, Rick Guest, Sergei Polunin, What Lies Beneath | Comments Off on Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath

Rick Guest, What Lies Beneath & The Language of the Soul

Still and moving images are the only ways of getting close to representing a memory of dance and it is only with the relatively recent development of recording techniques that the moving image has reliably captured artists in performance. The still image has been around for a lot longer, long enough, for example, to admire the series of photographs of Vaslav Nijinsky by Baron Adolphe de Meyer begun in 1911. In his sumptuous book of these photographs, Nijinsky Dancing, Lincoln Kerstein claims ‘Nijinsky is in fact the first dancer in history who seems to have collaborated consciously with a photographer on the level of art.’ Until the arrival of the 35mm camera and more sensitive film, the studio was where dancers and photographers would collaborate on a shared aesthetic but as soon as the technology was available dance photography turned its attention to the performance shot. Photographs of Royal Ballet dancers over the years show both kinds of images by such notable photographers as Gordon Anthony, Cecil Beaton, Anthony Crickmay, Michael Peto, Zoë Dominic, Keith Money, Lord Snowdon and Leslie Spatt while today you are likely to see glossy performance shots in the program by Johan Persson or Bill Cooper while in the contemporary sphere Hugo Glendinning and Chris Nash have developed a distinct style of expressive dance portrait that borrows from both performance and the studio. But at the end of last year fashion photographer Rick Guest released two self-published books of dance photography that eschews the performance for a more personal approach. Guest was introduced to dance by his wife some 15 years ago — he remembers Irek Mukhamedov in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet — and found his way back to The Royal Ballet with a commission to photograph principal dancer Edward Watson. From this grew the first book, What Lies Beneath, for which Watson is the muse and in which Guest’s fascination with and admiration for the dancer’s ethos finds expression in large-format portraits of an extended cast from The Royal Ballet, English National Ballet, the Danish National Ballet, Dresden’s Semperoper Ballett, Wayne McGregor’s Random Dance and Richard Alston Dance Company.

To concentrate his (and our) attention on the person Guest removes the locus of these photographs. All that outwardly signifies the dancer is the clothing, which is a study in itself: tattered, worn-out warmers that hang, it has to be said, with remarkable effect on these honed bodies or lovingly stitched repairs on a favourite unitard — as in the portrait of Melissa Hamilton that reveals the unequivocally trained body beneath its delicately scarred covering. In stripping the dancers of their performative role Guest reveals the enigmatic presence within. They are suspended not spatially (there are some fine examples of those, notably of Sergei Polunin suspended on an invisible cross) but psychologically; some have the confidence to be themselves in front of the lens, others feel the need to pose, giving the photographer their ‘best angle’ or baring their extraordinary physique for all time. But many are revealing of a quality that transcends description, of a neutral mien that is like the clay before it becomes a sculpted form (notably Svetlana Gileva and Julia Weiss of Semperoper Ballett). In other portraits there is an earthy quality that contrasts with the stage presence. Marianela Nuñez has a weightless, ethereal quality on stage but here she is quintessentially a woman with gravity in images whose locus is somewhere between the living room and the studio.

The dancers return our gaze — the gaze of the photographer — in response to a dialogue we cannot hear. Watson, like Hamilton, allows the gaze in, without any sense of defense. Eric Underwood looks into it as in a mirror; Yenaida Zenowsky and Yuhui Choe match it enigmatically, Alison McWhinney wistfully; Sergei Polunin meets it head on and Olivia Cowley gently deflects it. In Tamara Rojo’s reflective pose her eyes look away and down, preoccupied with her own world that is encapsulated within her superbly honed lines.

It is interesting to compare the physicality of dancers across the different companies — the effect of respective repertoires, physical conditioning and company culture. At Semperoper, for example, the dancers’ bodies appear more at ease and their clothing neatly utilitarian yet the traces of their profession are still apparent. What Guest has captured, essentially, is the way embodied classical training and the experience of performing express themselves in the eyes, in the posture and gesture of the dancer’s body. At the current exhibition of Guest’s photographs at the Hospital Club in Covent Garden, where the portraits are almost life-size, it is the eyes that engage directly with the lens and the spectator so they seem to follow you around the gallery.

In 2010 Guest saw Jane Pritchard’s Diaghilev exhibition at the V&A where his interest in fashion overlapped with his fascination for dance. The second compilation of photographs, The Language of the Soul, includes the same dancers as in What Lies Beneath but in more active poses partnered with his familiar world of fashion. ‘Some of the images are pure dance, some more fashion and some more photographic in nature,’ he writes. In both the dance and fashion portraits there emerges, unlike in What Lies Beneath, a performative quality which in certain cases is transformative.

There is a lovely anecdote in Sarah Crompton’s afterword to What Lies Beneath about Antoinette Sibley’s first glimpse of Galina Ulanova in rehearsal in 1956 that sums up the kind of place these dancers take up in Guest’s book:

“This old lady got up from the stalls. We thought she was the ballet mistress. She was saying something to the dancers and then she went and stood on the stage up on the balcony and she still had these awful leg-warmers on and, well, she looked 100. And then she suddenly started dreaming. And in front of our very eyes — no make-up, no costume — she became 14. I have never seen anything, in any sphere, as theatrical as Ulanova getting up in her scrubby old practice clothes…with her grey curly hair and becoming Juliet….From then on…I knew you could be…an amazing ballerina…and not perfect. Perfection was not part of Ulanova’s scene at all. She was human. It was to do with transformation.”

There are no ‘old ladies’ of either gender in the book, but some of the portraits reveal this transformative ability, notably in Sergei Polunin. He is singing in his portraits; he has something to sing about and so does his body. He becomes someone else. It is also good to see the performance photograph of Johannes Stepanek in an image I have seen in a Royal Opera House program without finding a credit.

The more I look at the photographs in these two fine compilations the more I am drawn into them. It is too easy to take the performance image for granted: to acknowledge the dancer without seeing the person. What Guest does is to first decontextualize the dancer and then to show each one in a refreshingly unfamiliar light with the immediacy of bringing the viewer into the same room to share his sense of admiration and awe.

http://rg-books.com/products