Compagnie Niya, Gueules Noires, Breakin’ Convention, Sadler’s Wells

Posted: July 23rd, 2022 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Abderrahim Ouabou, Breakin' Convention, Compagnie Niya, Gueules Noires, Jérémy Orville, Matthieu Maniez, Rachid Hedli, Romuald Houziaux, Sébastien Pouilly, Valentin Loval | Comments Off on Compagnie Niya, Gueules Noires, Breakin’ Convention, Sadler’s WellsCompagnie Niya, Gueules Noires, Breakin’ Convention, Sadler’s Wells, April 29, 2022

Opening the Sadler’s Wells Breakin’ Convention program, Compagnie Niya presented Geules Noires choreographed by the company’s founder Rachid Hedli. ‘Gueules noires’ is a French slang term for miners, but it has a double meaning: coal soot as a physical characteristic is conflated with the slang term ‘Pieds Noirs’ designating the North African origin of many of the miners. Hedli knows what he is describing because he grew up within a mining community: his late father — to whom this work is dedicated — worked in the declining years of the Nord-Pas de Calais mining basin.

Founded in 2011, Compagnie Niya comprises four dancers of North African heritage — Abderrahim Ouabou, Jérémy Orville, Valentin Loval and Hedli. Gueules Noires is Hedli’s first work for the company, constructed as a lyrical valedictory to his father as well as a choreographic treatment of the physical and social conditions of the mining environment. Lurking in the background is the broader issue of France’s post-colonial immigration policy, of which his father and Hedli have first-hand experience. While the politics are implicit in the subject, the emotional charge of the work derives principally from the love and respect Hedli feels for his father. His more objective view of underground working life, the camaraderie between the miners, and the relationships between them and their bosses, appears in the details.

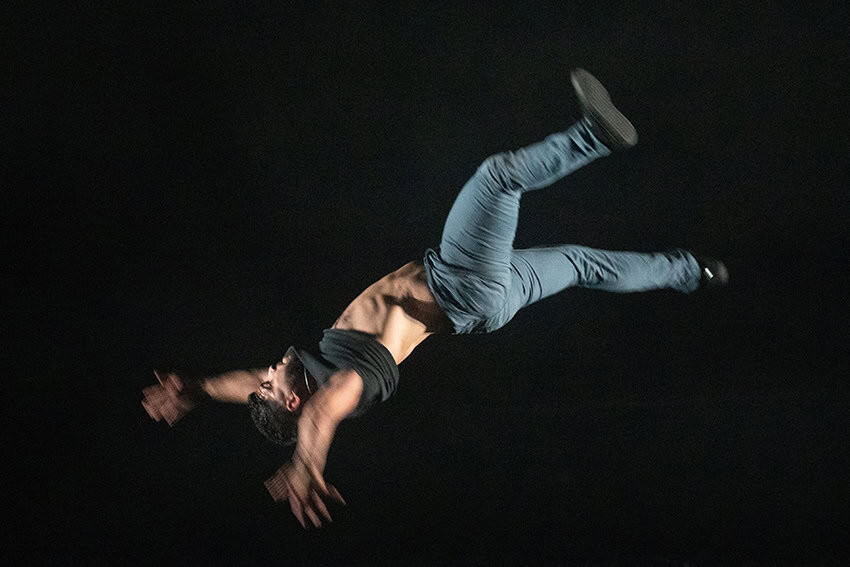

Hip hop is not an intrinsically narrative form of dance; it began outside in the street as a competitive display of virtuosity among and between individuals. Its origins are also closely related to rap music. Contemporary forms of hip hop retain both these elements —rap music and virtuosity — in varying degrees, but Compagnie Niya here eschews rap and uses hip hop as just one element in its narrative structure. Hedli’s choreographic language identifies strength, precision and rhythm — vital elements in working a coal face — while his theatrical elements — set, lighting and sound — suggest the underground environment. It is indicative of this experiment in fusing hip hop with narrative that the two strands remain parallel throughout, never quite merging; if you were to take away the contextual imagery from the hip hop sequences in Gueules Noires they would be a display of virtuosity, closer to their street origins.

The imagery of Gueules Noires is articulated in Sébastien Pouilly’s sound design and Matthieu Maniez’ lighting of the (unattributed) set. Pouilly uses a rumbling, subterranean soundscape while Maniez uses shafts of light to isolate characters and to delineate space. The set can be divided by light into an antechamber where the miners change into their working jackets, the mining face itself or a narrow precinct in which a violent confrontation takes place. For more intimate gatherings, Romuald Houziaux plays his own compositions on an accordion.

But even if Hedli’s hip hop sequences don’t merge choreographically with the narrative elements, they function in a cinematic sense, like sound on a film reel: Hedli has the theatrical maturity to be able to layer all the elements of the performance to form a highly integrated whole. At times the dancers’ actions come into vivid focus, as in the dramatic dance of the miners’ head lamps, or in the scene of violent, stone-throwing resistance to the management. At others the choreography, sound and light act together in unison to create the images we see. Whether highlighted or integrated into the narrative, the dancers display a sincerity in how they perform — not outwardly to the audience but focused inwardly on the content of their work, linking their movement with elements of the aural and visual environment. One senses that all we see and hear, with its beginning and end, has been going on and will continue to go on whether we are watching it or not; this is the illusion of a continuum that Hedli effectively creates.

The one overt reference to migration is in the ritual building of a small hearth at the end of Gueules Noires which is both poignant and ambiguous: does it represent the making of a home in a new country (assimilation) or a longing for the original home (national identity)? Compagnie Niya, as well as its language of hip hop, is similarly in the process of integrating itself into the French — and increasingly global — cultural environment. Hedli and his colleagues are very much in the present, using theatre as a powerful means of both remembering the past and imagining the future.