Posted: June 1st, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Anusha Subramanyam, Ash Mukherjee, Asian Arts Agency, Breathe, Erhebung, Jeff Lowe, Kamala Devam, Mayuri Boonham, Pavilion Dance, Power Games, Seeta Patel, Shane Shambhu, South Asian Dance Summit, Subathra Subramaniam, Under My Skin | Comments Off on South Asian Dance Summit

South Asian Dance Summit, Pavilion Dance, May 17-18

The Art of Defining Me photo: Peter Schiazza

The purpose of the 24-hour South Asian Dance Summit presented by Pavilion Dance South West and Asian Arts Agency was to demystify South Asian dance for presenters and producers by allowing them to get up close and personal with the traditional form and contemporary developments. What the summit achieved was to take South Asian dance out of its cultural, indigenous box and to put it on display as a communicative art. Paradoxically, it was seeing Seeta Patel interpreting Marvin Khoo’s Bharatanatyam solo, Dancing My Siva — with all its cultural associations — that put the entire summit in perspective. Here was a classical dance form with its unmistakable sophistication in gesture and rhythm that has been developing for hundreds of years; the way Patel danced it communicated effortlessly a beauty and an excitement that was timeless. At the same time the performance contextualised the efforts by other summit choreographers to derive a contemporary form.

Of the full-length works, Subathra Subramaniam’s Under My Skin takes gesture from another kind of theatre (that of the operating room) as its inspiration in her challenge to ‘the traditional boundaries between clinical practice and dance’. Where Subramanian dips in to the Bharatnatyam form becomes a point of self-identification, a vestige of a glorious past that has nevertheless embraced the present. In his latest work, Power Games, Shane Shambhu adopts the gestures of the trading floor in his comic-strip style story of the rise and fall of a market trader and in Erhebung, Mayuri Boonham marries the sculptural form of the body with a rigid sculptural framework by Jeff Lowe, resulting in a meditative play of movement against stillness, of ripe fruit on a tree.

The summit also presented ChoreoLAB2, a series of shorter works that are still in development. Subramaniam takes her inspiration for a solo from observations of mental illness; in Breathe, Ash Mukherjee crashes deliriously into the traditional form to see what remains; Anusha Subramanyam retains the humanity of the narrative form to depict the humanity of Aung San Suu Kyi and finally Seeta Patel and Kamala Devam play devil’s advocate in a short film called The Art of Defining Me. It raises impertinent yet pertinent questions for audiences and presenters alike, for while it thumbs its nose at cultural claustrophobia and narrow mindedness (as does Seeta Patel’s series of vignettes, What is Indian Enough?), its light-hearted approach effectively transforms our perceptions.

The summit organisers were keen to provide ample opportunities for dialogue between artists and presenters and to cross-reference the dance with other practices. In the lobby of Subramaniam’s Under My Skin were a bespoke tailor, Joshua Byrne, and the surgeon Professor Roger Kneebone (Subramaniam’s collaborator on the project), both of whom demonstrated their respective forms of hand gesture. What the summit showed is thus a broad, interrelated universe of creative expression showing not only the origins but also the new directions of the traditional form. We should not be impatient; we do not have the time to see the development of these forms over the next hundred years, but both past and future exist in the present moment, and that is where the summit unequivocally placed us.

Posted: April 5th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Jon Beney, LOL (Lots of Love), Luca Silvestrini, Parsifal James Hurst, Pavilion Dance, Protein, The Quay School, Valentina Golfieri, xoxo | Comments Off on Protein: xoxo

Protein: xoxo, Pavilion Dance, March 22

Sarah aloft in xoxo rehearsal

XOXO is the written equivalent of kisses and hugs but there isn’t much time for the relationship to develop: Luca Silvestrini and his three dancers from Protein have just three weeks to create a work with specially picked students from The Quay School in Poole and Hamworthy. It is part of Protein’s Real Life Real Dance participatory program, supported by The Monument Trust, Pavilion Dance South West, wave arts education agency and The Quay School. The students, Jamie, Rhys, Jordan, Holly and Sarah are the second group this year, after a partnership between Protein and artsdepot in London in January.

Silvestrini has derived xoxo from LOL (Lots of Love), his company’s very successful work about love and communications in the online social media age. He adapts parts of it to the students, but keeps the thread of LOL going with his own dancers, Valentina Golfieri, Jon Beney and Parsifal James Hurst (PJ).

I arrive for the second week of rehearsals. The first week apparently went really well but week two begins slightly differently. The Quay School supports young people who are at risk of exclusion from mainstream schools. Some disruptive behavior manifests in the studio, so that at any one time there is a charge of both creativity and negativity among the students; when the latter cancels out the former, the two accompanying teachers take time out to encourage the students back in to the studio. This takes its toll, as one person’s outburst affects everyone else, and in the meantime choreography has to be learned. The atmosphere can be fragile on both sides, but the goal of performance remains, which is why the project is so important. Silvestrini and his dancers manage to keep the project on track with pep talks, encouragement, and vast amounts of patience and respect.

The second day I attend, the atmosphere has improved dramatically; the studio is full of energy and drive, although one of the students wasn’t able to come in on that day due to illness. One of the Protein dancers takes his place and new sections are learned. As well as choreography, the students are asked to talk about their online experiences, to offer their brand of chatter to be recorded and used in the performance. By the end of the day a lot has been accomplished and all seems well.

I return the following week to see the show, but am sad to learn that one of the students who had shown so much promise couldn’t be involved with the performance at the last minute. She cannot be replaced at short notice so Silvestrini adapts the piece again. I can’t imagine too many choreographers who can deal with this kind of instability and uncertainty, but he does, brilliantly, as do his dancers and the remaining students.

The theatre is full of family, friends and school staff. There is lots of chatter and laughter. PJ wanders on to the stage from the audience with a tangle of red and yellow computer cables over his shoulder. There is a loud short-circuit, a flash of light and all goes black. Out of the darkness each student appears on a screen at the back of the stage; they are each at a keyboard looking into the camera so it looks as if we are watching them from the screen. Rhys, Sarah, Jamie and Jordan gather in a group at the front of the stage as we hear Valentina’s voice reading their online messages, chats and status updates. They then watch PJ and Valentina’s keyboard duet from LOL. It is movement that communicates immediately, and with the score of computer and keyboard sounds (it’s clearly not a Mac), it’s witty and accessible. Online dating goes livid with Valentina having a fit in computer time when Jon intervenes between the two. Gradually the students shed their nerves and take their places with the company members in movement and text. There is a sofa at the back where Jamie takes a rest. A couple of teachers appear on the screen with anecdotes from a day in the life at school. Rhys and Sarah dance a duet, PJ runs fast around the stage with Valentina and Jon to form two teams with the students on either side of the stage. Jumping over each other (with PJ’s extraordinary elevation he could jump easily over two people at a time), the performers circle Jamie in the centre, while Jordan takes a moment to smile at his Mum. PJ brings more cables into the centre on which Jordan rests. His mother, who we see talking on screen, says she’s still on his friends list while Jordan mimes gaming on stage. Xoxo is all about communicating in the internet age, but is also about social values: the students agree they don’t want a friend that judges a book by its cover.

Very soon it is all over. Cheers and applause from a proud and appreciative audience. Jamie whistles his relief. PJ and Jon bring the sofa to the front of the stage on which the students relax as if they own it. Valentina brings flowers for each, and Luca a present. Sarah and Rhys look so confident: trust and confidence are the rewards of this project. Jordan has learned teamwork and more capabilities. Jamie puts what he has learned into one word: skillage.

At the backstage reception afterwards the sense of pride, achievement and relief is palpable. Sarah and Rhys want to continue dance classes. But more than that: in an age of online chatter, non-verbal dance has found a way to bring out the characters and personalities of these students. It has not always been easy, but Silvestrini and his dancers have showed what is possible with patience, persistence and the right kind of moves. xoxo

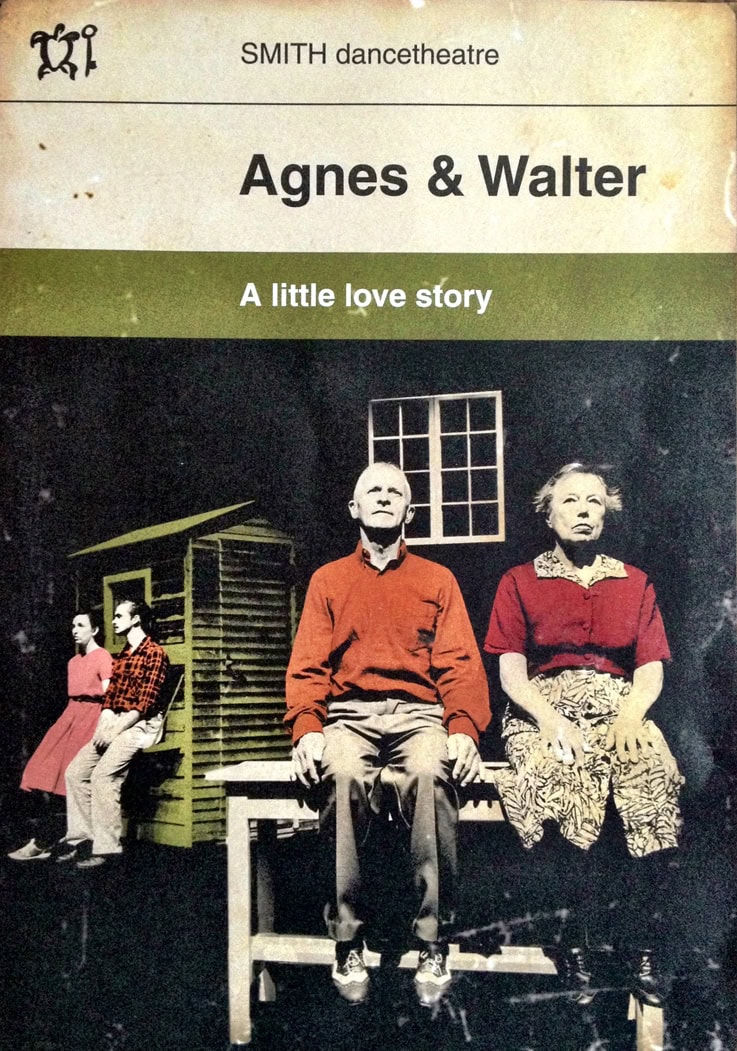

Posted: December 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Dan Canham, Elizabeth Taylor, Kate Rigby, Margaret Pikes, Neil Paris, Pavilion Dance, Ronnie Beecham, Sarah Lewis, Smith Dance Theatre | Comments Off on Smith dancetheatre: Agnes & Walter, A Little Love Story

Smith dancetheatre, Agnes and Walter: A Little Love Story, Pavilion Dance, November 8

I had the pleasure of seeing Smith dancetheatre in Neil Paris’ Agnes & Walter: A Little Love Story at Pavilion Dance at the beginning of November. Pavilion Dance has a great venue for smaller-scale dance and a thoughtful, engaging program. The front-end team of Deryck Newland and Ian Abbott nurture their dance and their public in ways that may encourage BBC arts editor, Will Gompertz, to modify his elitist slant on the benefits of arts funding. But back to Agnes & Walter.

I was sure Dan Canham and Sarah Lewis were going to speak in the opening section; language is so close to the surface of their movement that it seemed inevitable it would materialize, but nobody says a word. In that eloquent, perfectly-timed opening sequence Paris introduces the absent-minded, clean cut Walter (Canham) standing at a pale blue table dreamily running a string of Christmas lights through his fingers, checking them without looking. His wife, Agnes (Lewis), in a dress and apron is resignedly sweeping sawdust from the ground around the garden shed (which later doubles as a gingham-curtained house) as if she has done it many, many times before. There is a sense of nostalgia in the costumes (by Kate Rigby) and the set (lit nostalgically by Aideen Malone), a return to what is perceived as a homely set of values and an almost naïve sense of the goodness of life. Walter gets to the end of the string of lights, puts them down and crosses to the shed as Agnes comes over to the table to check the lights for herself (we are not the only ones to think Walter is absent-minded). A few moments later Walter emerges from the shed covered in sawdust, emptying it from his pockets and spreading it at every footstep. Seeing this, Agnes commits hara-kiri in slow motion with a kitchen knife right there on the pale blue table to a melodramatic Hollywood horror score. Walter immediately springs into action as the surgeon in his plastic safety goggles, saving his patient with consummate skill: pulling out the knife, plugging the hole, sedating the patient and stitching her up. He checks her vital signs, has to resort to shock treatment and succeeds in reviving his patient to a sitting position. She falls back but Walter applies his healing hands to her chest; she gestures ‘mouth to mouth’ to the romantic surgeon, so he inflates her by degrees until she reverts to life. She palpitates her heart with a fluttering hand, expresses a certain sadness that the play is over and starts to clean up.

All this makes perfect sense when you know that Agnes & Walter is based on James Thurber’s short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It is an inspired realization, and although it never again approaches its inspiration so purely as in this opening scene, Agnes & Walter confidently develops its own variations with Thurber-like humour. There is the couple of Walter and Agnes in older age, in which it is Agnes (Elizabeth Taylor) to whom her husband’s earlier absentmindedness seems to have migrated. She dances a poignant solo in which she appears to be in a dream, dancing around a maypole, waving at everyone, gathering spirits from the air, pulling them down to her lips as she rises up on tiptoe to meet them. Walter in older age (Ronnie Beecham) is as spry as his wife used to be, maintaining a risk-taking active life, finding pleasure in canoeing on the roof of the shed (as his wife wheels it across the stage) or in performing a rip-roaring dance with a pair of bunny ears around his neck. If this is the golden age, bring it on.

Weaving between the two couples is the figure of their guardian angel or spirit (Margaret Pikes), helping to resolve their problems and lending their narrative an emotional quality that derives from her voice: she does not sing her songs, she lives them, particularly Léo Ferré’s Avec le temps. In fact, music throughout Agnes and Walter – from Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man to Bruce Springsteen to Henryk Gorecki – provides an emotive backbone that reinforces the dance.

Paris’s choreography grows from the ground on which the characters stand, developing from the stillness of a thought into a phrase, just as Walter Mitty’s reveries were sparked from something he saw on his excursion to the shops. With Canham, the thought lingers unhurriedly before the movement develops but Lewis is more spontaneous. Responding to the wind (generated on stage by a 1950s-style standing fan) and to the second movement of Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, she immediately lets down her hair, breathing in deeply, stretching up in ecstasy, her arms dancing up in the air, head raised, smiling, aspiring. She stands on the table to get higher, lets go, and falls to the floor, yet after each collapse, she clambers back to the source of the wind. Feeling the air in her face and hands again, she reaches like a young child pulling spirits from the air (a recurring theme in Agnes & Walter), before the wind finally dies out.

If at first the two Agneses and Walters seem to pass across each other as different couples, towards the end they become superimposed in a quartet of coexisting ages. Canham develops a theme from sweeping the floor into a reverie of uncertain movement; Beecham joins in with his own variation on Canham’s theme. They stumble together, both finishing with arms raised and sitting on the table side by side with their backs to us in touching unity. Pikes, leaning against the shed, sings her final song, Springsteen’s My Father’s House: ‘I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts.’ Taylor and Lewis step pensively on to the stage, step together, step together; Canham and the smiling Beecham gradually join in. Pikes opens the door of the shed and puts up Walter’s Christmas lights in the doorway while Canham and Lewis begin a variation on a theme of making up (this is, after all, a little love story). Lewis lures Canham into the shed, closes the door and turns off all the lights.

There is something about the image of Agnes and Walter in the publicity material that is immediately appealing. In its colouring and content it contains all the elements of the work: its beguiling charm, its emotional range, its generational range, its down-to-earthness and even its literary provenance. It might have its origins in a bygone age, but the reach of the performance draws inspiration from the air and has room to breathe, making the characters in Agnes and Walter never less than fully alive and fully present.