Dance Umbrella 2019: Out of the System Mixed Bill at Bernie Grant Arts Centre

Posted: December 27th, 2019 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: Becky Namgauds, Dance Umbrella 2019, Ffion Cambell-Davies, Freddie Opoku-Addaie, Jonzi-D, Michael Mannion, Out of the System, Théo Inart, Theo TJ Lowe, Tyrone Isaac-Stuart | Comments Off on Dance Umbrella 2019: Out of the System Mixed Bill at Bernie Grant Arts CentreDance Umbrella 2019: Out of the System – Mixed Bill at Bernie Grant Arts Centre, October 22

Out of the System is a guest-programmed section of Dance Umbrella; for the past three years it has been curated with characteristic flair by Freddie Opoku-Addaie who described it in 2017 as ‘the presence of diverse dance cultures within vocational and non-vocational structures outside the regular framework of dance presentation’. Two years later Out of the System has worked its way into the system with the Big Pink Vogue Ball at Shoreditch Town Hall and a mixed bill at, and presented in partnership with, Bernie Grant Arts Centre. With five artists over four works, the mixed bill consists of small-scale works with large-scale themes of identity and racial politics that Opoku-Addaie characterises in public transport terms (influenced by his commute on a No. 26 Routemaster bus between Waterloo Station and Hackney Wick) as telling ‘complex journeys that are routed in the shared struggle, continuous stop/start but dealt with a crafted overview of human fortitude.’

Theo TJ Lowe (THÉO INART) has worked with Hofesh Schechter and Akram Khan, among others, and this shows in his compelling presence on stage in his solo, Fragility in Man – Part 1. He makes his entrance through the doors of the theatre on to the stage that resembles a bare waiting room with three chairs; ill at ease, he takes a seat like a patient waiting to be examined or, more ominously, a suspect about to be interrogated. There is something simmering or explosive in his succession of halting gestures and periods of stillness that respond to human commands, the barking of dogs or the cocking of a gun. The trauma of past violence extends out from behind his eyes to land somewhere on a vertical plane between us, like a two-way mirror; he shines a light on the audience but sees only his own reflection. Even behind a superhero mask he cannot hide his vulnerability because he is turned inside out; when he exits through the same doors he entered, he leaves behind him the fragile landscape of his being.

Like Lowe, Becky Namgauds turns herself into an exhibit, Exhibit F, tracing figures back and forth across the stage with her swirling, naked torso and long hair like a brush gradually filling in the paper with lines and colour. She is not so much building up a figure — the space is not like paper and releases the image as soon as it has passed — so much as laying down her emotional ground in repetitive patterns. What is exhibited and what is not is the constant issue in Exhibit F in which costume, movement and Michael Mannion’s lighting are fluid factors. Namgaud’s work, according to the program, deals with ‘recurring themes of feminism, femicide and the environment.’ There is no object in Exhibit F; it is its own constantly transforming subject.

Breaking the solo format, Ffion Campbell-Davies enters at the start of Beyond Words, vocalising high on the shoulders of Tyrone Isaac-Stuart while he blows a cool saxophone below. Beyond Words questions the framework of a colonial approach to black dance through ‘a journey between two people communicating matters of the heart’. Beginning as a procession, it disintegrates to the sound of machinery into images of physical oppression and struggle that lead to questions of self-worth and respect. Campbell-Davies and Isaac-Stuart confront a broad canvas of history and social significance, from ancestry and tribal affinity to the idea of home, with a sense of residual frustration. At the end, perched once again on Isaac-Stuart’s shoulders, Campbell-Davies asks the audience, ‘Who are you standing on?’ It’s a question, ironically, that Opoku-Addaie’s curation over the last three years has set out to answer.

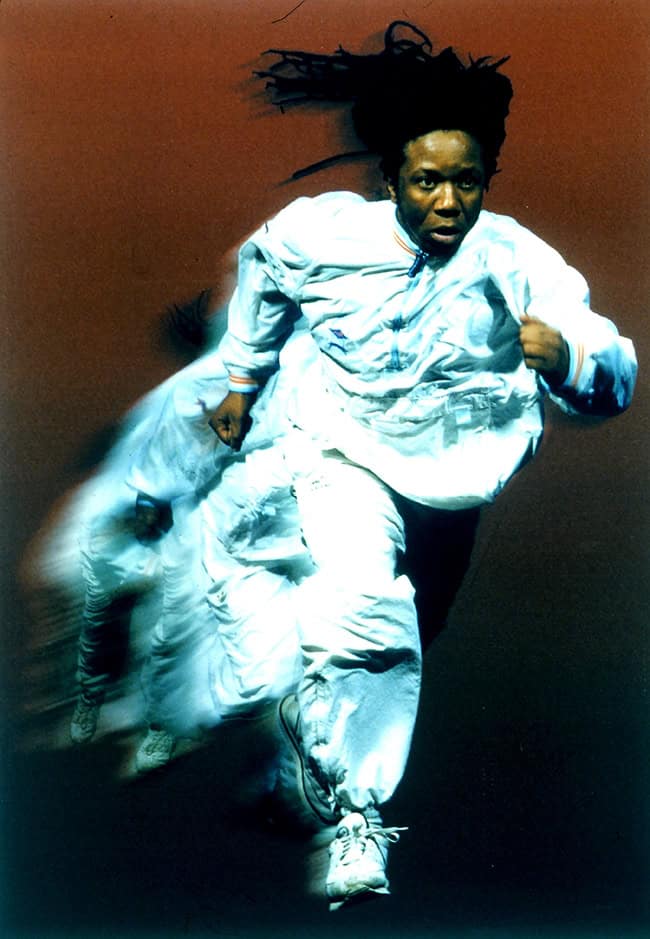

Jonzi-D’s Aeroplane Man, created in 1999 ‘but sadly still resonating today’, is founded on a similar frustration but ends in a more measured affirmation. His finely-honed parable of identity and cultural politics pulls no punches and makes its point in keen satire and brilliant mimicry. Born and bred in the East End of London, he is both pilot and passenger traveling in his Adidas trainers to search for his ‘own country’ at the unceremonious urging of one of his white colleagues. His air miles take him from Grenada (‘my mother’s land, not my motherland’), to Jamaica, the Bronx and Zululand, but wherever he lands he finds he is not quite genuine enough. With the running refrain of ‘Call up Mr. Aeroplane Man, Yeah Man, Yeah Man’, he returns to London to discover ‘this brown frame has found his name.’