Posted: June 18th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Dan Canham, Ian Morgan, Laura Dannequin, Malcolm Rippeth, Neil Paris, Ours Was The Fen Country, Spring Loaded, Still House, The Place, Tilly Webber | Comments Off on Still House / Dan Canham: Ours Was The Fen Country

Still House / Dan Canham: Ours Was the Fen Country, The Place, June 7

Ours Was The Fen Country. Photo © Still House

‘The relationship between human beings and the earth is very complex, but it is not something remote from our daily lives. Rather, the people/earth relationship is involved in everything we do, and it affects every aspect of our experience….’ So wrote Tsunesaburo Makiguchi in his 1903 treatise A Geography of Human Life, and Dan Canham would agree. He takes the relationship between the flat land of the Fens and the people who have lived there for generations, farming, fishing, trapping and surviving the windswept, desolate, sinking countryside as the starting point for his choreographic exploration, Ours Was The Fen Country. The Fens are where Canham grew up, so the piece is both a revisiting of familiar geography and an autobiographical ode to the landscape and culture that formed him, distilling the people and places into an essence with which we can feel an emotional connection with an indelible sense of respect and humility.

Canham has already explored the notion of place as common denominator between dance and geography in his idiosyncratic history of a derelict theatre in Limerick, 30 Cecil Street, in which a building is a proxy for the town; in Ours Was The Fen Country, it is the Holme Fen Post that is a proxy for the entire countryside. The original cast-iron column, represented on stage by a wooden post, was sunk into the fen in 1852 till its top was flush with the peat surface. It now rises some four metres above ground level, a metaphor for a disappearing way of life.

Canham shares this project with three other performers, all attuned to its physical and spiritual nature: Neil Paris, Tilly Webber and Ian Morgan. Canham and assistant director, Laura Dannequin, conducted the interviews that form the raw material of the work over a period of two years, cycling or taking trains to seek out the colourful characters who people Ours Was The Fen Country and who reveal as much about themselves as the land on which they live: an indication of the trust they invested in their two interviewers, a trust that will be returned later this month when Canham and company perform Ours Was The Fen Country in some of the communities where these people live (see www.stillhouse.co.uk for dates). There’s the man who makes and lays willow traps for eels, the cattle farmer concerned about the viability of his farm, the stress counselor who gives her son the heebie-jeebies, the stableman who has shaken hands with seven members of the Royal Family, and the daughter who feels she is seeing the end of the traditional way of life. Canham holds up a mirror to their lives, like a painter who sees and develops the identifying characteristics of his subject on canvas, but he also honours them.

The recorded conversations are disembodied voices, but Canham pulls the disembodiment out of the ether and on to the stage by the way the performers inhabit the characters. We hear the words on different layers: the original interview, the same words spoken by one of the performers or lip synced; sections of conversation may alternate all three techniques, and at other times they will overlap to provide different emotional reactions. Canham, who has done the brilliant work of editing the interviews, has mined the conversations for their nuggets of wisdom and insight, and sets them in a textual framework like gemstones on a ring. At the beginning it is Webber who personifies a woman who wonders why anyone would want to learn more about the Fens, then Paris speaks about the village he lives in, Canham about Sutton Market and Morgan about the closeness of the rural communities. This is the neutral documentary style, the vanilla flavor, on top of which Canham layers additional techniques as the work progresses. There are projections of the countryside overlaid with verbal descriptions (‘flat’ is a word that comes up frequently) and a little history of the transformation of the marshland into agricultural land, and even into political land: Paris reminds us this is Cromwell country, with a portrait of the independent, cussed and awkward parliamentarian on the screen looking remarkably similar to Paris (without the warts).

Each performer is synchronized with the other three — and with the recordings — through individual iPods with earphones. For those who have seen 30 Cecil Street, the setup will be familiar, with a computer and speakers on a table at the side (updated technology from the reel-to-reel machine), timber to demarcate the performing space, chairs to sit on and some 4×4 fence posts to build a frame for the makeshift projection screen: all redolent of a summer fair on the green, a small-scale countryside laid out before us under Malcolm Rippeth’s lighting and beautifully costumed by Dannequin. But it is in the dance that I feel Canham has taken the documentary to new levels of power and poetry. There are no steps that could be characterized as ballet or modern, contemporary, hip hop or jazz; the movement finds its form from the sometimes percussive and sometimes lyrical rhythms of the recorded speech, from the hesitancies of expression as much as from the sly humour. It is dancing to the voice as an instrument, incorporating body-at-the-pub gestures and personality ticks extrapolated into rhythmic steps and forms. There is a sense that the steps emerge only when needed as an additional layer of emphasis or colour, and always echo in their groundedness the ties to the earth. When Webber’s character speaks, she looks and thinks with her, head back, arched back, tensed shoulders and turned-in feet, her stress evident before she starts to move. All the men look at her until they stand up swaying as if the world is turning too fast. Canham is aware of the fissures in this rural way of life (his title is in the past for good reason) and places himself both inside it and outside, inhabitant and commentator. The four characters look at each other, exchanging positions, keeping eye contact. Two fall to the ground then get up, before they all lurch backwards, balanced on the edge, on the brink. Canham begins a simple gesture of slowly creaking back on his chair, until all four performers seem to be riding in place. Moving off their chairs, advancing slowly, they keep the rhythm while Webber articulates her arms and head so expressively within their minimalist range. The music takes on a unifying role as its rhythms urge the characters to find new ways of moving forward together. Keeping their focus on each other, they circle the stage, their steps getting bigger, anchored in the music, now turning, now jumping in place, an optimistic, joyous expression of ‘yes’ in the obdurate shadow of the Holme Fen Post.

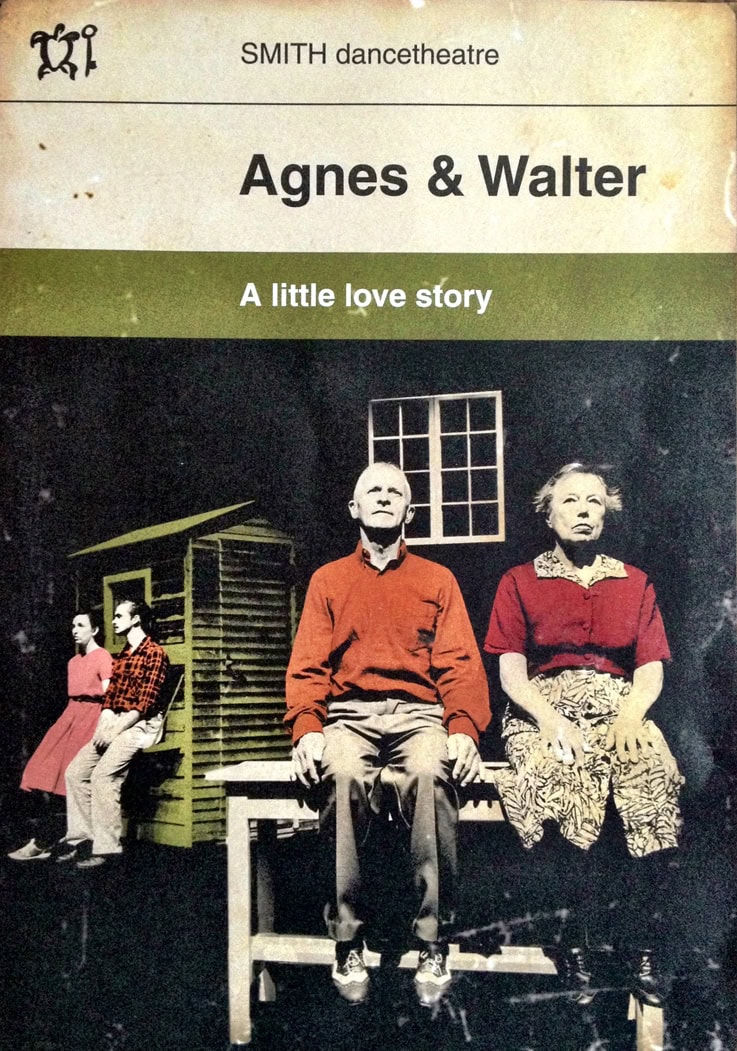

Posted: December 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Dan Canham, Elizabeth Taylor, Kate Rigby, Margaret Pikes, Neil Paris, Pavilion Dance, Ronnie Beecham, Sarah Lewis, Smith Dance Theatre | Comments Off on Smith dancetheatre: Agnes & Walter, A Little Love Story

Smith dancetheatre, Agnes and Walter: A Little Love Story, Pavilion Dance, November 8

I had the pleasure of seeing Smith dancetheatre in Neil Paris’ Agnes & Walter: A Little Love Story at Pavilion Dance at the beginning of November. Pavilion Dance has a great venue for smaller-scale dance and a thoughtful, engaging program. The front-end team of Deryck Newland and Ian Abbott nurture their dance and their public in ways that may encourage BBC arts editor, Will Gompertz, to modify his elitist slant on the benefits of arts funding. But back to Agnes & Walter.

I was sure Dan Canham and Sarah Lewis were going to speak in the opening section; language is so close to the surface of their movement that it seemed inevitable it would materialize, but nobody says a word. In that eloquent, perfectly-timed opening sequence Paris introduces the absent-minded, clean cut Walter (Canham) standing at a pale blue table dreamily running a string of Christmas lights through his fingers, checking them without looking. His wife, Agnes (Lewis), in a dress and apron is resignedly sweeping sawdust from the ground around the garden shed (which later doubles as a gingham-curtained house) as if she has done it many, many times before. There is a sense of nostalgia in the costumes (by Kate Rigby) and the set (lit nostalgically by Aideen Malone), a return to what is perceived as a homely set of values and an almost naïve sense of the goodness of life. Walter gets to the end of the string of lights, puts them down and crosses to the shed as Agnes comes over to the table to check the lights for herself (we are not the only ones to think Walter is absent-minded). A few moments later Walter emerges from the shed covered in sawdust, emptying it from his pockets and spreading it at every footstep. Seeing this, Agnes commits hara-kiri in slow motion with a kitchen knife right there on the pale blue table to a melodramatic Hollywood horror score. Walter immediately springs into action as the surgeon in his plastic safety goggles, saving his patient with consummate skill: pulling out the knife, plugging the hole, sedating the patient and stitching her up. He checks her vital signs, has to resort to shock treatment and succeeds in reviving his patient to a sitting position. She falls back but Walter applies his healing hands to her chest; she gestures ‘mouth to mouth’ to the romantic surgeon, so he inflates her by degrees until she reverts to life. She palpitates her heart with a fluttering hand, expresses a certain sadness that the play is over and starts to clean up.

All this makes perfect sense when you know that Agnes & Walter is based on James Thurber’s short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It is an inspired realization, and although it never again approaches its inspiration so purely as in this opening scene, Agnes & Walter confidently develops its own variations with Thurber-like humour. There is the couple of Walter and Agnes in older age, in which it is Agnes (Elizabeth Taylor) to whom her husband’s earlier absentmindedness seems to have migrated. She dances a poignant solo in which she appears to be in a dream, dancing around a maypole, waving at everyone, gathering spirits from the air, pulling them down to her lips as she rises up on tiptoe to meet them. Walter in older age (Ronnie Beecham) is as spry as his wife used to be, maintaining a risk-taking active life, finding pleasure in canoeing on the roof of the shed (as his wife wheels it across the stage) or in performing a rip-roaring dance with a pair of bunny ears around his neck. If this is the golden age, bring it on.

Weaving between the two couples is the figure of their guardian angel or spirit (Margaret Pikes), helping to resolve their problems and lending their narrative an emotional quality that derives from her voice: she does not sing her songs, she lives them, particularly Léo Ferré’s Avec le temps. In fact, music throughout Agnes and Walter – from Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man to Bruce Springsteen to Henryk Gorecki – provides an emotive backbone that reinforces the dance.

Paris’s choreography grows from the ground on which the characters stand, developing from the stillness of a thought into a phrase, just as Walter Mitty’s reveries were sparked from something he saw on his excursion to the shops. With Canham, the thought lingers unhurriedly before the movement develops but Lewis is more spontaneous. Responding to the wind (generated on stage by a 1950s-style standing fan) and to the second movement of Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, she immediately lets down her hair, breathing in deeply, stretching up in ecstasy, her arms dancing up in the air, head raised, smiling, aspiring. She stands on the table to get higher, lets go, and falls to the floor, yet after each collapse, she clambers back to the source of the wind. Feeling the air in her face and hands again, she reaches like a young child pulling spirits from the air (a recurring theme in Agnes & Walter), before the wind finally dies out.

If at first the two Agneses and Walters seem to pass across each other as different couples, towards the end they become superimposed in a quartet of coexisting ages. Canham develops a theme from sweeping the floor into a reverie of uncertain movement; Beecham joins in with his own variation on Canham’s theme. They stumble together, both finishing with arms raised and sitting on the table side by side with their backs to us in touching unity. Pikes, leaning against the shed, sings her final song, Springsteen’s My Father’s House: ‘I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts.’ Taylor and Lewis step pensively on to the stage, step together, step together; Canham and the smiling Beecham gradually join in. Pikes opens the door of the shed and puts up Walter’s Christmas lights in the doorway while Canham and Lewis begin a variation on a theme of making up (this is, after all, a little love story). Lewis lures Canham into the shed, closes the door and turns off all the lights.

There is something about the image of Agnes and Walter in the publicity material that is immediately appealing. In its colouring and content it contains all the elements of the work: its beguiling charm, its emotional range, its generational range, its down-to-earthness and even its literary provenance. It might have its origins in a bygone age, but the reach of the performance draws inspiration from the air and has room to breathe, making the characters in Agnes and Walter never less than fully alive and fully present.

Posted: September 26th, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: A Short Lived Alteration of an Existing Situation, Ben Wright, Copter, Darren Ellis, Neil Paris, Nina Kov, Revolver, The Devil's Mischief, The Place Prize | Comments Off on The Place Prize semi-final 3

photo: Benedict Johnson

The Place Prize semi-final 3 (Nina Kov, Neil Paris, Ben Wright, Darren Ellis), The Place, September 20

There’s a buzz of excitement in the front row as we notice a model helicopter on the very front of the stage. The copter’s blades flutter briefly in response, perhaps, to the stage manager calling ‘places’ just before the lights go down. Nina Kov, choreographer and the other performer in Copter, settles down on the floor in the dark. The first flood of light projects a silhouette of the copter on to the backdrop, to a suitably throbbing, reverberating soundscape by Paul Child that sounds as if it was recorded in the depths of a real copter. Then our little star whirs into action within its own spotlight. Copter is essentially a duet and solo variations between Kov and the copter, thanks to the pilot and battery charger, Jack Bishop, (who remains in the wings throughout). Lucy Hansom lights the stage perfectly to keep the diminutive, buzzing copter visible at all times as it flies its missions. Bishop can land the copter on Kov’s hand, fly it between her legs and fly it just out of reach when Kov tries to retrieve it. As you may have guessed, all the attention is on the copter, which Kov imbues with character by virtue of her interaction with it. At one point Kov rescues the copter, sets it on its skids for it to make its escape, and at another she blows it from her hand, like a bird. At times her arms appear to command the copter, and at others the trajectory of the copter influences hers. We easily forget that it is Jack Bishop in the pilot’s seat. The closest we get to being inside the copter’s eye is when Bishop pilots a sturdier model to carry a tiny camera that projects images on to the screen. So much for the copter; but what of the participation of Kov herself? If her final, heroic image of whirling around a large blade above her head is meant to suggest a transference of life from the copter to the human, Kov’s movements have not prepared us sufficiently to make this jump of the imagination. Her movement phrases bear little relation to any evolutionary process, and her costume (by Alice Hoult) belongs more in the studio than on the airfield. There is something, however, in the interaction between Kov and the copter that works; Bishop is a skilled pilot, but can he teach Kov how to fly?

In the pause, the stagehands place lots of milky-white conical paper hats on the stage with seemingly random precision. It’s like a designer moonscape, lit by Aideen Malone. The backdrop is a light red digital projection by Dan Tombs with a floating amoeba-like image at the top that makes me feel I’m looking up at the surface of the water from inside the tank. It’s the last time I notice it. Carly Best creeps in wearing an identical conical hat with a big letter D. None of the other hats on the stage seem to have letters. Best surveys the hats, crouching down to examine them as if visiting a graveyard. Sarah Lewis enters from the other side; she has a G on her hat. Dolce and Gabanna? No, the Devil and God, for this is Neil Paris’s The Devil’s Mischief, based on the book of the same name by Ed Marquand.

There is an obvious tendency to see the two women as punished schoolchildren sent to sit on their stools in their respective corners, but their identities suggest a broader scenario: instead of being the dunces, they are the progenitors of this sea of ignorance and common misunderstandings that divide them. Having arrived in their separate roles, in similar styles and colours of clothes (by Kate Rigby), they now realise, rather sheepishly, that it’s time to resolve their differences and act in unity. With palms up, Best steps among the cones, carefully at first, but as her confidence and assurance grow her limbs start to dislodge the cones in jabbing, fleeting spasms of emotion that have the quality of a human puppet – Petrouchka comes to mind. The more phlegmatic Lewis, overcoming an initial hesitation, joins forces with her erstwhile rival and they manage to overturn many, but not all the cones. There is very little physical contact between the two, but at the close of The Devil’s Mischief, the caps of G and D touch in a gesture of solidarity and embrace.

Paris’s choreography and the accompanying music – the beatless soundscape of Stars of the Lid’s Apreludes (in C Sharp Major) and Jolie Holland singing the hauntingly beautiful ballad Rex’s Blues – together create a dream-like meditation on the nature of good and evil (how closely those words resemble god and devil), too open-ended to go through to the final of The Place Prize, but a lovely essay on form that will, I am sure, resurface somewhere else in SMITH dancetheatre’s work.

Ben Wright’s bgroup entry is another essay, Short Lived Alteration of an Existing Situation, on a theme of the common ephemerality of dance and music, according to Wright’s entry video. He talks of ‘playing with the moment where sound and movement respectively move away from and into the constancy of silence and stillness.’ The stage has no edges, apart from the light that Guy Hoare provides, which is soft at its circumference, suggesting infinity beyond. The inside of this circle of light is an arena, in which Sam Denton and Lise Manavit perform. To begin with, a red curtain of light (suggested by Alan Stones’ sound with Hoare’s dramatic lighting) cuts off our visibility of the interior, and as it fades we see Denton on all fours crawling forward, animal-like, then running backwards in his circle of light and coming to an upside down stasis on his shoulders and head. The primitive imagery continues with Manavit’s beating her chest, rippling through her torso, and rather dispassionately engaging with Denton as they test and extend each other’s limits. There is a moment when Manavit picks Denton up from flat on the ground to rest on her lap, an amazonian feat that, for sheer power and fluidity, takes the breath away.

It is difficult to avoid ascribing a narrative to the action, and it is probably not what Wright is interested in here. For ten minutes he creates a flow of movement that ‘defies the inevitable pull of gravity and immobility’, just as a musical phrase defies silence. There is very little movement for movement’s sake in Wright’s duet; one phrase flows thoughtfully into another, without the use of choreographic prepositions, creating a flowing, sculptural dynamic which he sustains in silence. Then there is a magical moment when John Byrn’s playing of the opening chords of Rachmaninov’s Prelude (in B Minor, op 32 No. 10) merges with the movement like a swimmer entering water. The emotional quality of the Prelude seems to affect the two dancers, or, to be more accurate, to affect my interpretation of the relationship of the two dancers. What is clear is that the music and dance are mutually reinforcing. This change is perhaps the short-lived alteration of an existing situation in the title, which continues until the repeated, sonorous note at the end of the Prelude after which the curtain of light comes down once again and the duet fades into oblivion. I feel Wright still has ideas he wants to develop in this work; he will, but for now he has left us with a miniature gem of pure dance that needs an appropriate setting.

Darren Ellis’s Revolver (from the Spanish, not the wild west) is just that, a sequence of turning motifs, always clockwise (I read that; I wouldn’t have noticed) by two unstoppable dancers, Hannah Kidd and Joanna Wenger to a rock guitar accompaniment by The Turbulent Eddies. The two guitars provide the constant (read relentless) rhythmic patterns, within which Kidd and Wenger perform their variations. Costumed in white phosphorescent dresses and tops (an in-house collaboration between Ellis and Kidd) and lit by Lee Curran, they begin a first, accelerated sequence in strobe lights (to slow it down) followed by three more sequences that get gradually smaller and quieter. They then extend the first sequence, and with a change in the music, they each move to their respective circles of light, executing sequences in harmony, in counterpoint, adding to them, varying them, and changing direction, but always in a clockwise direction. That and the guitar thrust are the two constants, apart from the energy of Kidd and Wenger that flows out from the stage into the audience. Ellis suggested in his original submission that the two women would transform and morph into one another, a concept taken from Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, but the psychological nature of the idea has been dropped in favour of a purely physical treatment within a mathematical framework. Impressive as Kidd and Wenger are, one wonders what Revolver might become with a Bergman treatment.