Dance Umbrella 2019: Oona Doherty at Southbank Centre and The Yard Theatre

Posted: October 21st, 2019 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: Ciarran Bagnall, David Holmes, John Scott, Oona Doherty, Sam Finnegan, Southbank Centre, The Sugar Army, The Yard Theatre | Comments Off on Dance Umbrella 2019: Oona Doherty at Southbank Centre and The Yard TheatreDance Umbrella 2019: Oona Doherty at Southbank Centre and The Yard Theatre.

In a welcome programming decision, Dance Umbrella includes two works by Belfast-based choreographer, Oona Doherty. One is Hope Hunt and The Ascension Into Lazarus at The Yard Theatre in Hackney Wick and the other is Hard to Be Soft at Southbank Centre. Doherty created Hope Hunt first, in 2016, but the two works are like cousins; the family resemblance is clear while the gene pool is shared. What binds them together is the common canvas on which they are created: life in Belfast. Doherty has lived in the Northern Irish city for the past 20 years and knows it intimately; she also has a proclivity for researching the rougher side of life. There’s a rawness to her work that has no truck with artifice; she’s not interested in translating her experiences into choreography but in embodying them on stage. At the same time her performance effortlessly channels the elements of violence and anger into a paradoxical sense of freedom; her gravitational pull to the floor is equalled by her quicksilver ability to rise from it.

Hope Hunt and The Ascension Into Lazarus is concentrated Doherty, serving as both inspiration and reference for Hard to Be Soft. The biblical figure of Lazarus, whom Jesus miraculously raised from the dead, serves for Doherty as an enduring metaphor to champion the disaffected male youth of Belfast she portrays. By juxtaposing the soundtrack of recorded confrontational conversations from the Belfast streets with seventeenth century choral church music — Allegri’s sublime Miserere — Doherty’s body is constantly charged with contrasting impulses; her gestures are imbued with the hurled aggression and frustration of the conversations, while they equally aspire, or ascend, to some finer, ineffable state reflected in the music. The pleasure of seeing the performance is how Doherty invokes these two inputs, sometimes separately and sometimes together but always playing between them like separate monodies that she combines into a harmonious line. She achieves this because she is a rare combination of accomplished dancer and mimic; her expressive facial features and gestures engage in the conversations we are hearing with candid clarity and make us laugh at the accuracy of her observation, and then her fluid dance body will overlay a response to the music to suggest a spiritual context. As a performer she is nowhere other than on the streets of Belfast and she draws us to them, and to their stories, with an immediacy as if we were there too.

Hard to Be Soft broadens her canvas while maintaining the same metaphor; she describes it as ‘a physical prayer celebrating all that we have and an invocation for what we are missing.’ Doherty divides her performance into four episodes — ‘a cinematic sci-fi stations of the cross’, as she has called it — in which she performs the first and last episodes as solos, but has choreographed the middle two respectively on a group of sassy young women — The Sugar Army — and two bare-chested men — John Scott and Sam Finnegan — whose meaty presence is both a bid to bring the physicality of Belfast directly to the stage and a welcome provocation to dance conventions. Her two solos anchor the work in the singular imagery of Hope Hunt, providing both a prologue (Lazarus and the Bird of Paradise) and an epilogue (Helium) to the central sections. The Sugar Army is a bevy of teenage girls recruited from each city with whom Doherty has spent a couple of weeks discussing identity in relation to mediatised attitudes towards beauty. To a soundscape beat by David Holmes, the Sugar Army inhabits the prêt-à-porter choreography with their youthful personalities and attitudes that don’t, however, quite match the delightful cynicism of a Belfast woman who describes ‘dressing up the politics of conflict with glamour’. In the third section, Meat Kaleidoscope, the presence of Scott and Finnegan correlates the power dynamic between a father and son with an expletive-strewn recording of a growling argument that echoes broader political tensions. The size and weight of the men, like two equally matched wrestlers, create their own form of physical dialogue that poignantly embraces antagonism and understanding in equal measure.

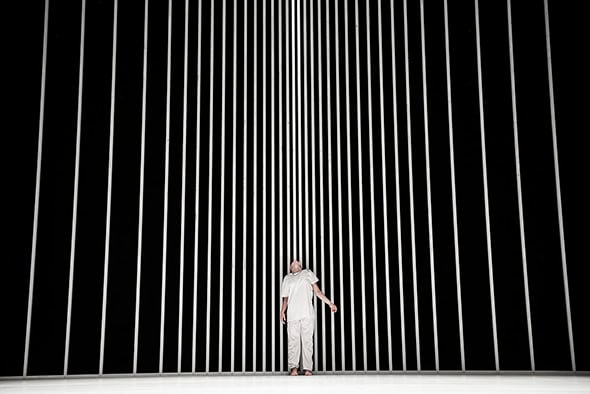

Given the physical and aural iconography of both works and the overt reference to Lazarus in each, it is hard not to acknowledge the religious signification of Doherty’s work that underpins the potential of the human body to unite earthly and spiritual opposites. Ciarran Bagnall’s set for Hard to Be Soft is made up of vertical steel columns that refer ambiguously to prison bars or cathedral architecture, while her lighting generates the upward aspiration towards the divine. Yet despite the religious allusion, there is no overt moralizing; Doherty’s earthy, streetwise persona consistently deflects it. The power of her work is in juxtaposing hard-hitting political imagery with a state of radiant belief. A line from the Helium section straddles the possibilities between the two: ‘What if Jesus came back? What if he was bricking your car on the Saintfield road?’