Rambert2: Triple Bill at Sadler’s Wells

Posted: November 19th, 2019 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Adam Carree, Andrea Miller, Artemis Stamouli, Crystal Pite, Damien Jalet, Emily Gunn, Frédéric Despierre, Hogan McLaughlin, Jermaine Spivey, Minouche Van de Ven, Nathan Chipps, Noemi Daboczi, Paul Keogan, Prince Lyons, Rambert2, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Vivian Pakkanen, Vladimir Zaldwich | Comments Off on Rambert2: Triple Bill at Sadler’s WellsRambert2, Triple Bill at Sadler’s Wells, November 5

This second year’s program of Rambert2 at Sadler’s Wells shows a sophistication and artistry, both in terms of choreography and interpretation, that one would expect of the main company, so it is worth remembering that Rambert2 is the practice component of an MA in Professional Performance Studies that Rambert School offers students through the auspices of the University of Kent. The quality of dancers is high because the Rambert brand can attract a large number of applicants to the course. One of last year’s students, Salomé Pessac, is now in the main company which gives an idea of the level of proficiency on offer. There is also an interesting transatlantic connection — four of the thirteen dancers and two of the three choreographers this year are American — through Rambert’s artistic director, Benoit Swan Pouffer.

Choreographer Jermaine Maurice Spivey has spent time in Crystal Pite’s company, Kidd Pivot, which is an indication of both his quality as a dancer and his good fortune in witnessing a bourgeoning choreographic talent at work; furthermore, he has deconstructed and reconstructed Pite’s works in order to set them on other companies. In Terms and Conditions, Spivey is experimenting with ideas of his own; he develops the work in sections, choreographically and musically, that are structurally connected but not yet coherent. It starts with words that are manipulated verbally and choreographically with an initial cue from Emily Gunn. A seated Nathan Chipps repeats the word with a variety of inflections and intonations while opposite him in another chair Minouche Van de Ven improvises movement to them. Costume designer Noemi Daboczi’s idea to embed flexible mirrors in the back of her white overalls initiates another section; the dancers later remove them and place them over their faces. It’s a visually arresting idea but doesn’t seem to lead anywhere and is quite impracticable in a section of Spivey’s head-tossing choreography. A final section relies on the repetition of a circular pattern with the dancers taking it in turns to lie like a victim at the centre while the others walk or run around. Terms and Conditions is an articulate study for a promising, but as yet unfulfilled contract.

Sin is a duet taken from the 2010 Babel by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui and Damien Jalet. Based on the struggle between Eros and Thanatos, it is a narrative with a straightforward formal structure that gradually inverts its opening position over its sinuous course. The connection between Prince Lyons as the male figure and Van de Ven as the female is intense and dramatically coherent; they could be complementary elements of each other in an internal battle for survival or separated as incompatible egos within a couple. From its title, Sin could also be understood as the story of Adam and Eve and the choreography uses snake-like imagery throughout. Whatever the interpretation, the two performers manifest a fateful attraction to each other that oscillates in a riveting yin-yang altercation between power and subversion. Adam Carrée’s lighting plays its own dramatic role that includes a large reflective surface descending obliquely from which the performers cannot hide.

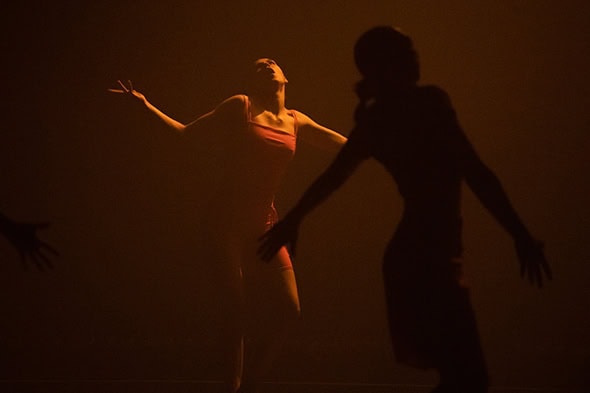

In her programme note for Sama, choreographer Andrea Miller, who is the artistic director of New York-based Gallim Dance, writes: ‘There are essential, ambiguous and complex elements of our humanity that can only be accessed through our physical experience.’ With its inherent capacity for physical embodiment, dance is fertile ground for elaborating the importance of our bodies in social discourse. For Sama, Miller and her creative team — lighting designer Paul Keogan, costume designer Hogan McLaughlin and composers Vladimir Zaldwich and Frédéric Despierre — delve deep into the realms of imagery and imagination to conjure up a paeon to physical expression, a sensuous and tangible whirl of theatrical and circus arts that the dancers elaborate with infectious abandon. At the heart of Sama is a lament for what Miller fears to be ‘the beginning of an apocalypse of the body’; at the beginning is an enactment of an Eastern parable and at the end a lullaby that follows an exultant jump into darkness by the dancers. Within this framework, perhaps the most significant role is for a young woman whose clearly articulated detachment could well be ‘the still point of the turning world’ from which all energy arises. Miller created it for Vivian Pakkanen but due to a last-minute illness she was replaced by an undaunted Artemis Stamouli from the previous cohort of Rambert2. That kind of coolness under pressure is what Sama celebrates.