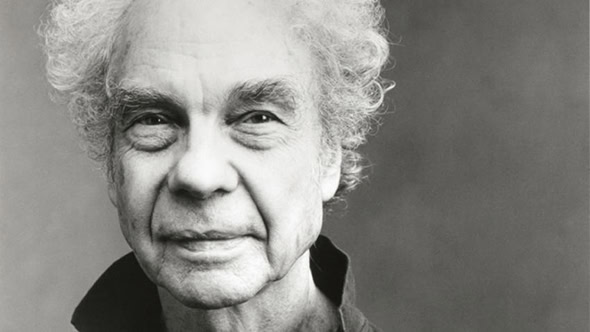

Ian Abbott at Dublin Dance Festival 2019

Posted: May 25th, 2019 | Author: Ian Abbott | Filed under: Festival, Performance | Tags: Andrea Palumbo, Angus Balbernie, Ashley Chen, Benjamin Perchet, Dublin Dance Festival, Irish Modern Dance, Jari Boldrini, John Scott, Judy Adams, Kevin Coquelard, Lucy Boyes, Matthew Collings, Maurizio Giunti, Mufutau Yusuf, Nicola Cisternino, Oona Doherty, Ramona Caia, Robbie Synge, Valda Setterfield, Virgilio Sieni | Comments Off on Ian Abbott at Dublin Dance Festival 2019Dublin Dance Festival 2019, May 15-17

Dublin Dance Festival 2019 is the penultimate edition under the curational control of Benjamin Perchet. Now in its 15th year, DDF is Ireland’s premiere contemporary dance festival, something akin to London’s Dance Umbrella: a city-wide festival with multiple partners and scales of work and a mixture of local and international guests. Sitting alongside Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker’s Rosas danst Rosas, Colin Dunne & Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Session, and Liz Roche’s I/Thou is a trio of works on consecutive nights that ask questions around gender and age.

La Natura Delle Cose (LNDC) by Virgilio Sieni is a problematic work. Created in 2008, LNDC features four male dancers (Nicola Cisternino, Jari Boldrini, Maurizio Giunti, and Andrea Palumbo) and one female dancer (Ramona Caia). According to the program ‘Sieni draws inspiration from the great poem De rerum natura by Roman philosopher Lucretius to explore “The Nature of Things”, portraying a character moving through the entire cycle of life in one hour. In a performance of overwhelming beauty, five dancers offer a counterpoint to what Lucretius believed to be the chief cause of unhappiness: the fear of death. Moving as a single body, they create a rich visual poem that presents the masked character of Venus at three stages of life. First as an eleven-year-old girl, she moves with graceful fluidity, borne aloft by the four male dancers. Later she explores the world as a two-year-old baby and finally she is an eighty-year-old woman, her descent complete.’

The reality is you have four men controlling, manipulating, positioning and restricting a female performer, pulling her legs apart, marking their hands on her body, and pawing her in three 20-minute scenes as she wears the masks of a teenage girl, a toddler and an 80-year-old woman. Caia is a gifted mimic, embodying the physical traits and stereotypical movements at all three stages of life; we see the toddler tantrum through rigid legs and resistance alongside the grace and subtle flow of the older body. There might be an alternative way to view this work as there was a little skill in not allowing Caia to touch the floor as the men caught, lifted and carried her around the stage in the opening scene. However, female bodies on stage are always political; what you do with them and how you frame them is a choice. When you choose to cover the female performer’s face for the entire performance while the men remain unmasked and give men total control, you are adopting a position of male power. The lack of awareness from both the choreographer and the festival that the work can be read in this way is startling; my response was not in isolation as conversations with other audience members across the festival identified levels of discomfort with and questions about the work presented.

Inventions by John Scott/Irish Modern Dance Theatre was considerably less problematic in its portrayal of women as it gave space for and a gift to Valda Setterfield and Oona Doherty; supported by Mufutau Yusuf, Ashley Chen and Kevin Coquelard, Inventions is ‘a new Bach-inspired dance work’ that ‘weaves new stories into an old ballroom setting, echoing the memory of dances past. In a series of duets Inventions focuses on two contrasting couples, one falling in love, the other falling into an abyss.’ Scott’s work is made in response to a tricky period in his life and the text and physicality has an urgency and clarity to it that come from a place of truth.

As a 60-minute suite of duets/solos with the occasional group moments we can smell the abyss, the rage and despair alongside the possibilities of redemption and hope. Scott has assembled five performers who are magnetic, engaging and infinitely watchable creating an environment in his studio that has unlocked something; to see exceptional dancers perform well is a moment of rare joy.

At the age of 85 Setterfield is the anchor, orchestrating a sense of calm amongst the emotional debris left by the others; Doherty is an exceptional presence on stage, part wolf, part shark, part hawk and there is an internal menace and trauma that is married to an exquisite technical control. In her duet with Chen towards the end of the work, they slam, run, fly, hold and compete with each other; even though Chen is taller and heavier there is no doubt that the power lies with Doherty.

Ensemble by Lucy Boyes and Robbie Synge is the result of a practice seven years in the making after Boyes challenged the status quo of the type of bodies people expect to see doing dance; with a startling bias towards bodies that are ‘professional’ and under 30 there is a dearth of middle-aged and older people on stage and in the mainstream media. Opening with a tightly choreographed 15-minute section we see Synge, Judy Adams, Angus Balbernie, Hannah Venet and Christine Thynne deliver an intricate set of floor work and knotted walking patterns to a driving score mixed by Matthew Collings. The remaining forty minutes comprises a series of duets between Synge/Venet and Adams/Thynne/Balbernie which foreground the ability and personality of the dancers.

Ensemble is refreshing for its lack of artifice; we see the dancers on the side of the stage, wiping down, taking on water and waiting for their stage time. This isn’t an engagement or outreach project for older people, but a quietly radical space where bodies come together to transmit joy, lightness and an authenticity that is infectious and demonstrates how different bodies can tell a different story. It immediately subverts societal expectations of what bodies in their 60s and 70s can achieve with a demonstration of strength, intimacy and togetherness.