Posted: April 30th, 2016 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Akram Khan, Anish Kapoor, Kaash, Kimie Nakano, Kristina Alleyne, Lighthouse Poole, Nicola Monaco, Nitin Sawhney, Sadé Alleyne, Sarah Cerneaux, Sung Hoon Kim, Yen-Ching Lin | Comments Off on Akram Khan Company, Kaash

Akram Khan Company, Kaash, Lighthouse Poole, April 13

Akram Khan Company in the revival of Kaash (photo: Jean-Louis Fernandez)

I had been invited by Libby Battaglia to give a writer’s workshop for young reviewers at Lighthouse Poole and the performance we were going to review was Akram Khan’s Kaash, his company’s first full-length work created in 2002. Presently on tour 14 years later, Kaash is an early and compelling vision of what the fusion between Khan’s classical kathak training and contemporary dance might look like. The result has the sophistication of the classical with the raw power of the contemporary that remains as thrillingly visceral as it evidently did in 2002 when it won the Critics Circle National Dance award for Best Modern Choreography. Performed by a typically international cast of five — then as now — the choreography has a universal quality unattached to any particular nationality or genre, but Kaash displays a unity of influence through the collaborations with artist Anish Kapoor and musician Nitin Sawhney. In their respective mediums both Kapoor and Sawhney had already established a synergy between their Indian roots and western culture so by the time of their collaboration with Khan his choreographic forms could be framed in an aural and visual environment that complemented and enriched them.

There is no linear narrative in Kaash but rather a series of ideas explored in movement, what the program note describes as ‘Hindu gods, black holes, Indian time cycles, tablas, creation and destruction.’ These are elements of Indian cosmology and dance familiar to Khan who was exploring the affects of his cultural identity without resorting to their traditional cultural signifiers. Images are woven into the fabric of the work, as in the form of the god Shiva glimpsed in a line of dancers, one behind the other, displaying the multiple arms of a single body, or the mudras (hand gestures) that carry their own meaning but here give shape to and refine the movements of the arms and hands. Indian time cycles or signatures are the kathak rhythmical counts that are chanted by the accompanying singer. When Khan himself was dancing in the original he would chant these time signatures himself, but here it is his voice we hear (recorded by Bernhard Schimpelsberger); it becomes part of the score rather than a live element of the dance.

Kapoor’s large black rectangle painted on the backdrop represents the black hole that in Indian cosmology was the centre of the world and the seat of Lord Vishnu, creator of the universe. A black hole is also a region of space-time with such strong gravitational effects that nothing can escape from inside it. The stage becomes a dynamic energy field, lit from smouldering to fire by Aideen Malone, inside which Khan’s choreography creates a powerful sense of gravity acting on the bodies of his dancers. One common characteristic of kathak and contemporary dance is the repudiation of vertical space; movement remains intensely horizontal and grounded. The dancers in Kaash cross from one side of the stage to the other like particles in close proximity. Even solos, especially by the (English) twins Kristina and Sadé Alleyne, have this remarkable vitality that cannot be extinguished. The figure of Sung Hoon Kim, bare-chested in a long black skirt (all costumes by Kimie Nakano), provides a soothing spiritual dimension — an exploration of Lord Shiva, agent of destruction and change. In Hindu cosmology the end of each kalpa brought about by Shiva’s dance is also the beginning of the next cycle. For some time in the opening section Kim remains still, absorbing the energy around him until he starts to move with extraordinary speed and precision, which in turn affects the other dancers; the cycle of creation and destruction continues unabated. Khan’s original role is danced by Nicola Monaco, and the fifth dancer is Sarah Cerneaux. The reconstruction of Kaash under the eye of rehearsal director Yen-Ching Lin has been guided by some of the original cast, though because the techniques of contemporary dance have changed in the last 14 years Kahn encouraged the present dancers to refresh the choreography without losing its overall form. This is perhaps why the work still seems so alive.

Sawhney’s score supports and gives life to the cyclical energy of Kaash, acting on our ears in the same way Kahn’s choreography immerses our visual and kinetic senses. Sawnhey makes use of drumming that belongs as much to the Japanese kodo as to the Indian tabla: powerful, percussive rhythms that emphasise the earthy quality of the dance pervading the first section with its repeated patterns of dynamic lunges and powerful, heavily sweeping arms. At one point the addition of John Oswald’s Spectre played by the Kronos Quartet, seeps into the score like a memory, and similarly there are whispered fragments of recorded speech that tease the notion of ‘kaash’ (Hindi for ‘if only’) into aural puzzles: “If only I’d bought one instead of two” or, more pertinently to Khan’s identity, “If I tell you the truth about who I really am.”

Kaash in 2002 was uniquely situated in the British cultural and social zeitgeist that sought links and bridges to its multicultural communities. Khan responded with a work that seemed to go far beyond that remit, turning it almost inside out. As the dramaturg, Guy Cools, has suggested, Khan’s artistic universe (along with that of Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui) is largely built around ‘his identity in-between dance cultures,’ and in this early work he effectively subsumes his two identities by fusing them into a seamless whole.

Posted: November 11th, 2013 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Allen Fisher, Archana Ballal, Bharatanatyam, Carl Pattrick, Chris Fogg, Gemma Bass-Williams, Roger Kneebone, Subathra Subramaniam, Under My Skin | Comments Off on Sadhana Dance: Under My Skin

Sadhana Dance, Under My Skin, The Place, October 18

Archana Ballal, Gemma Bass-Williams and Carl Pattrick in Under My Skin (photo: Marc Pepperall)

What we wish for sometimes manifests in ways that are as unpredictable as they are inexorable. Choreographer Subathra Subramaniam wanted first to be a doctor but found her expression in the classical Indian dance tradition of Bharatanatyam. Her latest work, Under My Skin, returns to her first love, which gives the title a certain ambiguity: it refers not only to what happens to a patient undergoing surgery but also to an emotional attachment that is hard to shake off, as in the Cole Porter song, I’ve Got You Under My Skin. Subramaniam’s involvement is both: undoubtedly passionate in transforming surgery into choreographic form, she also demonstrates a vicarious curiosity in the operating theatre through a program of simulations, craft demonstrations and haptics that precedes the performance.

Enter Dr. Roger Kneebone, professor of surgical education at Imperial College London, whose mission to disseminate a greater understanding of surgical procedures dovetailed seamlessly with Subramaniam’s research into Under My Skin and gives it a rich context. There is evidently no pain in Subramaniam’s work, nor the emotion of dealing with the balance of life and death — something that even the surgical simulations bring affectingly to the surface. Her skill is in extracting the beauty of the movement from the operating theatre and in interpreting the essential trust that is a perquisite for any surgical procedure. In doing so, she not only expands the boundaries of Bharatanatyam but provides Professor Kneebone with an expressive medium to further his own research.

Through the surgical simulations (staged at The Place as part of the Bloomsbury Festival) we begin to understand the critical importance of close and accurate communication within a team of specialists providing an acute level of care for a patient undergoing surgery. This will involve the surgeon, at least one assistant surgeon, a scrub nurse, an anaesthetist, and an OTP (operating theatre practitioner). Sometimes the team will meet each other for the first time around the operating table, but they must work meticulously and intimately on matters of vital importance to the patient. In the course of her research for Under My Skin, Subramaniam witnessed this teamwork as an observer, and although there are only three dancers in her work, their relationship to one another is as tightly choreographed as that of the operating theatre team.

As in other works of Subramaniam there is text, here a poem about the nature of blood by Allen Fisher, whom Professor Kneebone commissioned. Its clinically precise language takes on a sense of mystery in the recording of Chris Fogg’s sonorous voice emanating from the dark. The reading of the opening lines is superimposed on a single red light like a drop of blood under a microscope to the sound of baffles, plungers and artificial breathing apparatus, the beginning of a parallel collaboration between lighting designer Aideen Malone and sound artists Kathy Hinde and Matthew Olden.

Malone also observed the operating theatre environment (and as a consequence has been asked to propose improvements to the lighting system). Her three rectangular corridors of light form distinct environments for the three medical personnel (Gemma Bass-Williams, Archana Ballal and Carl Pattrick) in blue surgical scrubs (assimilated by Kate Rigby) who adjust imaginary controls and instruments with minute accuracy and concentration: three routines that develop freely and beautifully into extended dance movement. Ballal is clearly at home with the flow of Bharatanatyam that underlies the choreography — especially in her solo to the violin of Preetha Narayanan — and adapts the gestures of the operating theatre as if putting on a pair of latex gloves. Bass-Williams and Pattrick, while clearly immersed in the style, work towards the flow of Bharatanatyam from the task-based material. What unites the three dancers is the clarity and precision of their gestures.

As the trio merges into the central corridor of light, Malone expands it into one large theatre in which the trio breathes with the breath of an imaginary patient preparing for an operation. Taking the weight of, supporting and balancing each other’s body are all metaphors for the mutual dependency of the team.

Bass-Williams and Pattrick abstract the meticulous washing of hands and the precise order of gowning into a ritual dance. Malone’s lighting moves like a film from one scene to another; in the light at one moment is Ballal in a dynamic dance while in the semi-darkness the surgeons continue their preparation, a solo of life superimposed on a duet of support. The dance vocabulary immerses itself increasingly in the current of Bharatanatyam; Bass-Williams and Pattrick join Ballal in a trio of rhythmic turning steps accented with the deep plié and completed by the rich arm and hand mudras.

The focus is narrowed to a circle of yellow light in which we see — as if we are in the team — just the hands the colour of latex taking and placing instruments, sharing actions, cutting, stitching, checking, swabbing, and cleaning in a silent, concentrated rhythm. Subramaniam once again transforms these gestures away from the operating theatre into the performing theatre, adapting the ability of Bharatanatyam to tell stories through gesture and dance. One aspect that is less developed here is the traditional use of the face as an expressive instrument, especially the eyes. The dancers look at each other, but their eyes are not always eloquent.

An acceleration in the music returns us to Bharatanatyam’s rapid, rhythmic footwork; the influence of Indian classical dance is strongest here and the dancers are stripped down to their essential natures. This is the pleasure of movement where flow is everything; it feels like a coda of growing complexity and technical achievement, but Subramaniam returns us once again to the routine operating theatre where poetry is supplanted by the sounds of the machines, the broad wash of light by a circle of yellow light and dancing by a silent concentration on gestures of intimacy and healing. Pattrick finishes his task and leaves. Bass-Williams and Ballal stay on to accompany the patient’s recovery, then Bass-Williams hands over to Ballal whose head is bathed in the opening blood-red circle of light. She withdraws her head as Fogg’s voice intones the final lines, ending neatly with, “This is blood clotting that will help to save your life.”

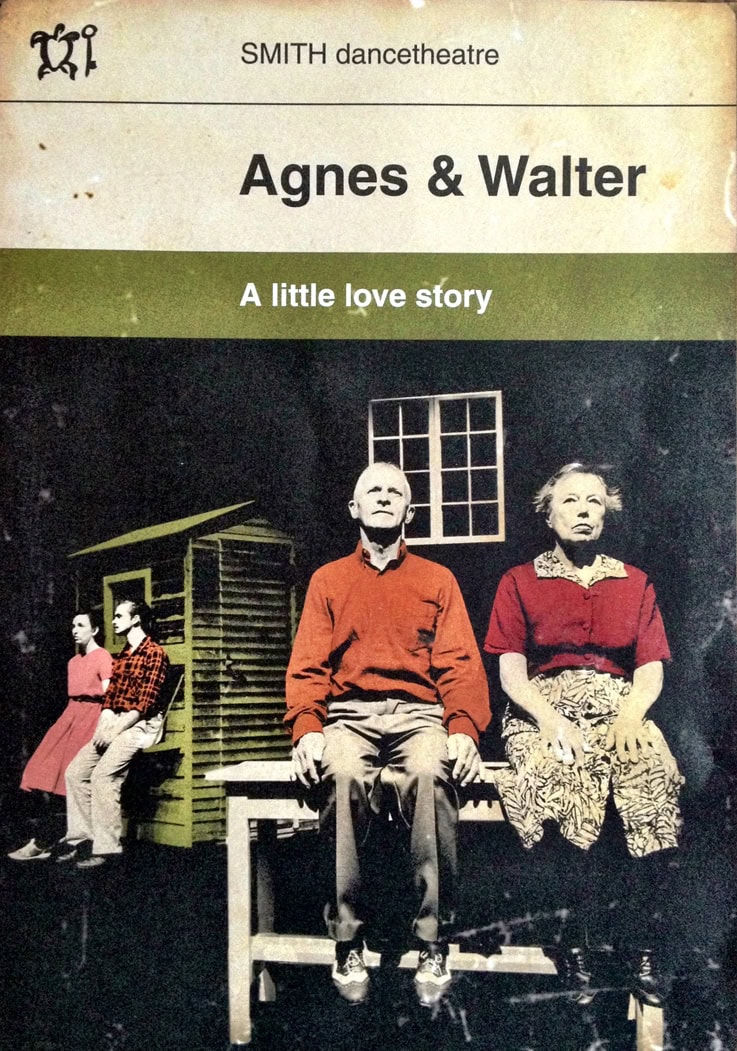

Posted: December 3rd, 2012 | Author: Nicholas Minns | Filed under: Performance | Tags: Aideen Malone, Dan Canham, Elizabeth Taylor, Kate Rigby, Margaret Pikes, Neil Paris, Pavilion Dance, Ronnie Beecham, Sarah Lewis, Smith Dance Theatre | Comments Off on Smith dancetheatre: Agnes & Walter, A Little Love Story

Smith dancetheatre, Agnes and Walter: A Little Love Story, Pavilion Dance, November 8

I had the pleasure of seeing Smith dancetheatre in Neil Paris’ Agnes & Walter: A Little Love Story at Pavilion Dance at the beginning of November. Pavilion Dance has a great venue for smaller-scale dance and a thoughtful, engaging program. The front-end team of Deryck Newland and Ian Abbott nurture their dance and their public in ways that may encourage BBC arts editor, Will Gompertz, to modify his elitist slant on the benefits of arts funding. But back to Agnes & Walter.

I was sure Dan Canham and Sarah Lewis were going to speak in the opening section; language is so close to the surface of their movement that it seemed inevitable it would materialize, but nobody says a word. In that eloquent, perfectly-timed opening sequence Paris introduces the absent-minded, clean cut Walter (Canham) standing at a pale blue table dreamily running a string of Christmas lights through his fingers, checking them without looking. His wife, Agnes (Lewis), in a dress and apron is resignedly sweeping sawdust from the ground around the garden shed (which later doubles as a gingham-curtained house) as if she has done it many, many times before. There is a sense of nostalgia in the costumes (by Kate Rigby) and the set (lit nostalgically by Aideen Malone), a return to what is perceived as a homely set of values and an almost naïve sense of the goodness of life. Walter gets to the end of the string of lights, puts them down and crosses to the shed as Agnes comes over to the table to check the lights for herself (we are not the only ones to think Walter is absent-minded). A few moments later Walter emerges from the shed covered in sawdust, emptying it from his pockets and spreading it at every footstep. Seeing this, Agnes commits hara-kiri in slow motion with a kitchen knife right there on the pale blue table to a melodramatic Hollywood horror score. Walter immediately springs into action as the surgeon in his plastic safety goggles, saving his patient with consummate skill: pulling out the knife, plugging the hole, sedating the patient and stitching her up. He checks her vital signs, has to resort to shock treatment and succeeds in reviving his patient to a sitting position. She falls back but Walter applies his healing hands to her chest; she gestures ‘mouth to mouth’ to the romantic surgeon, so he inflates her by degrees until she reverts to life. She palpitates her heart with a fluttering hand, expresses a certain sadness that the play is over and starts to clean up.

All this makes perfect sense when you know that Agnes & Walter is based on James Thurber’s short story, The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. It is an inspired realization, and although it never again approaches its inspiration so purely as in this opening scene, Agnes & Walter confidently develops its own variations with Thurber-like humour. There is the couple of Walter and Agnes in older age, in which it is Agnes (Elizabeth Taylor) to whom her husband’s earlier absentmindedness seems to have migrated. She dances a poignant solo in which she appears to be in a dream, dancing around a maypole, waving at everyone, gathering spirits from the air, pulling them down to her lips as she rises up on tiptoe to meet them. Walter in older age (Ronnie Beecham) is as spry as his wife used to be, maintaining a risk-taking active life, finding pleasure in canoeing on the roof of the shed (as his wife wheels it across the stage) or in performing a rip-roaring dance with a pair of bunny ears around his neck. If this is the golden age, bring it on.

Weaving between the two couples is the figure of their guardian angel or spirit (Margaret Pikes), helping to resolve their problems and lending their narrative an emotional quality that derives from her voice: she does not sing her songs, she lives them, particularly Léo Ferré’s Avec le temps. In fact, music throughout Agnes and Walter – from Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man to Bruce Springsteen to Henryk Gorecki – provides an emotive backbone that reinforces the dance.

Paris’s choreography grows from the ground on which the characters stand, developing from the stillness of a thought into a phrase, just as Walter Mitty’s reveries were sparked from something he saw on his excursion to the shops. With Canham, the thought lingers unhurriedly before the movement develops but Lewis is more spontaneous. Responding to the wind (generated on stage by a 1950s-style standing fan) and to the second movement of Gorecki’s Symphony of Sorrowful Songs, she immediately lets down her hair, breathing in deeply, stretching up in ecstasy, her arms dancing up in the air, head raised, smiling, aspiring. She stands on the table to get higher, lets go, and falls to the floor, yet after each collapse, she clambers back to the source of the wind. Feeling the air in her face and hands again, she reaches like a young child pulling spirits from the air (a recurring theme in Agnes & Walter), before the wind finally dies out.

If at first the two Agneses and Walters seem to pass across each other as different couples, towards the end they become superimposed in a quartet of coexisting ages. Canham develops a theme from sweeping the floor into a reverie of uncertain movement; Beecham joins in with his own variation on Canham’s theme. They stumble together, both finishing with arms raised and sitting on the table side by side with their backs to us in touching unity. Pikes, leaning against the shed, sings her final song, Springsteen’s My Father’s House: ‘I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts.’ Taylor and Lewis step pensively on to the stage, step together, step together; Canham and the smiling Beecham gradually join in. Pikes opens the door of the shed and puts up Walter’s Christmas lights in the doorway while Canham and Lewis begin a variation on a theme of making up (this is, after all, a little love story). Lewis lures Canham into the shed, closes the door and turns off all the lights.

There is something about the image of Agnes and Walter in the publicity material that is immediately appealing. In its colouring and content it contains all the elements of the work: its beguiling charm, its emotional range, its generational range, its down-to-earthness and even its literary provenance. It might have its origins in a bygone age, but the reach of the performance draws inspiration from the air and has room to breathe, making the characters in Agnes and Walter never less than fully alive and fully present.